511-action

Rick Gilmore

2021-10-29 11:24:31

For fun

Output types

- What types of outputs are there?

- How are they produced?

- By the muscles

- By the nervous system

- Outputs include

- Movements, vocalizations, facial expressions, gestures

- Autonomic responses

- Endocrine responses

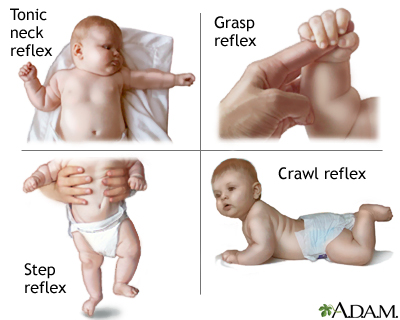

Types of movements

- Reflexes

- Simple, highly stereotyped, unlearned, rapid, acquired early

- vs. planned or voluntary actions

- Complex, flexible, acquired, slower

- Discrete (reaching) vs. rhythmic (walking)

- Ballistic (no feedback) vs. controlled (feedback)

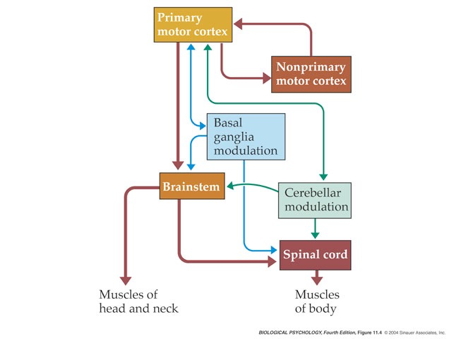

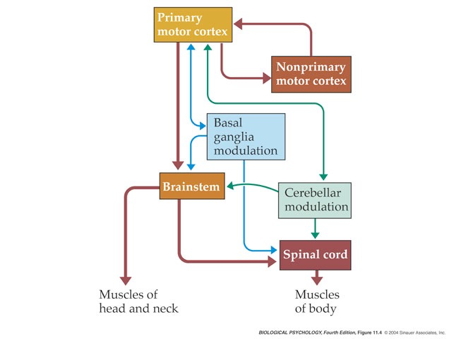

Motor system anatomy

Key ‘nodes’

- Primary motor cortex (M-I)

- Non-primary motor cortex

- Basal ganglia

- Brain stem

- Cerebellum

- Spinal cord

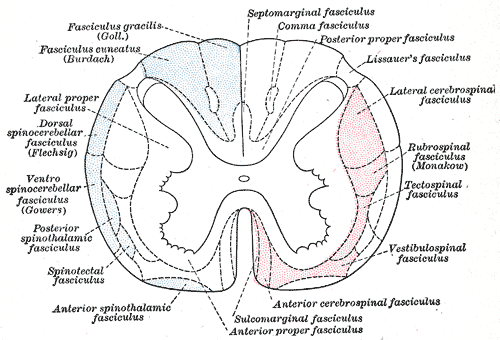

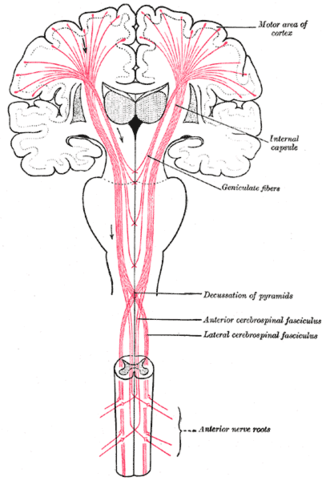

Projection pathways

- Pyramidal tracts

- Pyramidal cells (Cerebral Cortex Layer 5) in primary motor cortex (M1)

- Corticobulbar (cortex -> brainstem) tract

- Corticospinal (cortex -> spinal cord) tract

- Crossover (decussate) in medulla

- L side of brain ennervates R side of body

Source: Wikipedia

- Extrapyramidal system

- Tectospinal tract

- Vestibulospinal tract

- Reticulospinal tract

- Involuntary movements

- Posture, balance, arousal

Direct cortical control

- in humans; prevalence uncertain in other animals

- For individuated (“fractionated”) movements of fingers, toes, lips, but other muscles, too.

Figure 1. Evidence of corticomotoneuronal connections in human subjects. Indirect, noninvasive evidence of the existence of monosynaptic connections between corticospinal neurons and spinal motoneurons may be obtained in awake human subjects by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (b,c) and coherence analysis of either cortical [electroencephalogram (EEG)] and muscular activity [electromyogram (EMG)] (d,e) or two separate recordings of muscular activity (f). (b,c) Corticospinal neurons can be excited by a brief magnetic pulse applied by a magnetic coil placed over the appropriate part of the motor cortex in awake human subjects. If the intensity of the magnetic pulse is adjusted appropriately, the evoked descending volley in the corticospinal tract may elicit a subthreshold excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) in the relevant spinal motoneurons. This EPSP may be demonstrated as a change in the discharge probability of a single motor unit recorded from the muscle (b). In the illustrated example, the subject was asked to voluntarily activate the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle, and the discharges of a single motor unit were recorded by a needle electrode inserted into the muscle. TMS elicited a short-lasting (2-ms) increase of discharge probability at a latency of 45 ms (b). The short duration of this peak is consistent with the short rise time of a monosynaptic EPSP. This interpretation is further supported by the observation that stimulation of Ia afferents with known monosynaptic connections to the motoneurons elicits a peak with a similar short duration (c). Data in panels b and c modified with permission from Nielsen & Petersen (1994). (d,e) EEG recorded from the motor cortex and EMG recorded from a voluntarily activated muscle (TA in the illustrated example) show rhythmic modulation of the recorded activity at a frequency of 15–35 Hz. As shown from a coherence analysis of the two signals in panel d, some of this activity is common for the two sites, suggesting a close link between cortical and muscular activity. Panel e shows the EEG and EMG activities are not always synchronous but may show a time lag, which is in the range expected for a fast-conducting direct pathway to the motoneurons. Data in panels d and e modified with permission from Hansen et al. (2002). (f) A monosynaptic origin of corticomuscular coherence is further supported by the observation of short-term synchrony between the discharges of pairs of TA motor units, which may be related to the coherence in the 15–35-Hz frequency band. The subject was asked to voluntarily activate the TA muscle, and the discharges of two different TA motor units were recorded with needle electrodes. The short duration of the central peak of synchronization suggests that the motor unit activities are modulated by a common (monosynaptic) input from collaterals of last-order neurons, which are in all likelihood identical to corticomotoneuronal cells. The secondary peaks at lags of approximately 50–60 ms on either side of the central peak suggest that this last-order input modulates the discharge of the motor units at a frequency of about 20–30 Hz, i.e., corresponding to the coherence observed in the paired EEG-EMG recordings in panels b and c. Data in panel f modified with permission from Nielsen & Kagamihara (1994).

Muscles

- Generate forces

- In one direction

Functional classes

- Axial

- Trunk, neck, hips

- Proximal

- Shoulder/elbow, pelvis/knee

- Distal

- Hands/fingers, feet/toes

Agonist/antagonist pairs

Anatomical types

- Cardiac

- Striated (striped)

- Skeletal

- Voluntary control, mostly connected to tendons and bones

- Smooth

- Arteries, hair follicles, uterus, intestines

- Regulated by ANS (involuntary)

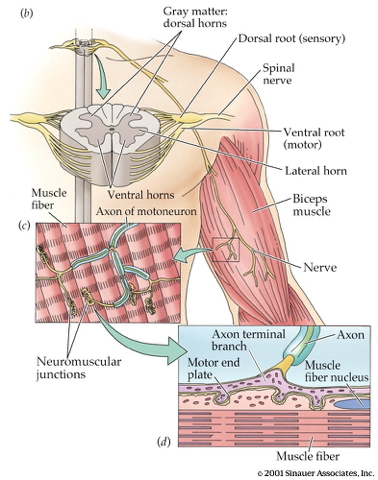

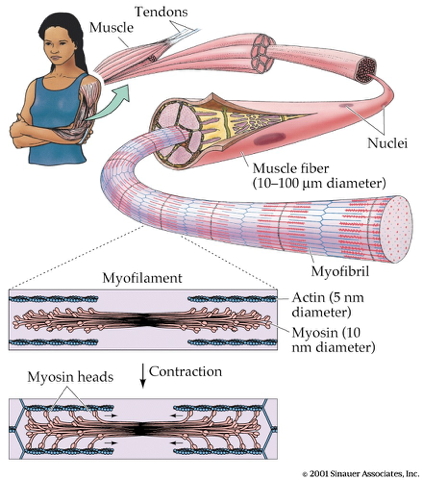

How skeletal muscles contract

- Motoneurons (somata in ventral horn of spinal cord)

- Project to muscle fiber

- Neuromuscular junction

- Synapse between motor neuron and muscle fiber

- Releases ACh

- Motor endplate

- Contains nicotinic ACh receptors

- Activation produces excitatory endplate potential

- Muscle fibers depolarize

- Depolarization spreads along fibers like an action potential

- Ca++ released from intramuscular stores

- Muscle fibers contain bundles of myofibrils called sarcomeres

- Myofibrils

- Contain actin & mysosin proteins

- “Molecular gears”

- Bind, move, unbind in presence of Ca++, adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

Skeletal muscle fiber types

- Fast twitch/fatiguing

- Type II

- White meat

- Slow twitch/fatiguing

- Type I

- Red meat

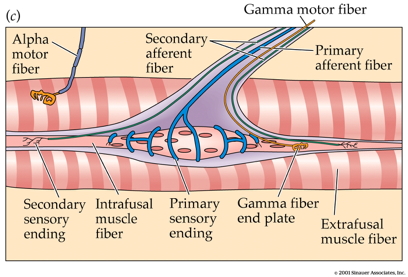

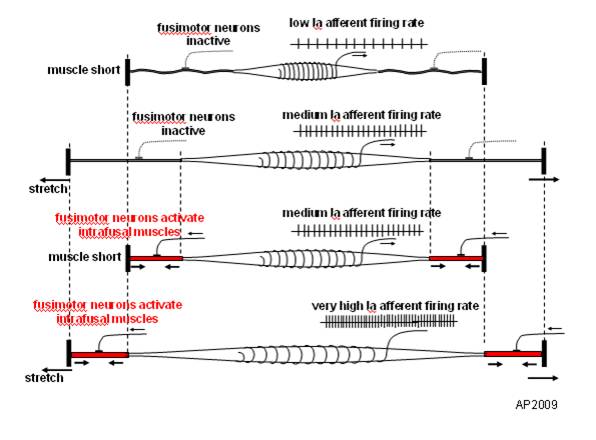

Muscles as sensory organs

Two fiber types

- Intrafusal fibers

- Sense muscle length and change in length, e.g. “stretch”

- Also called muscle spindles

- Provide muscle proprioception (perception about the self, a form of interoception)

- Ennervated by by primary Ia afferents (sensory output from muscle); also secondary Type II fibers

- Ennervated by gamma (\(\gamma\)) motor neurons (motor input)

- Extrafusal fibers

- Generate force

- ennervated by alpha (\(\alpha\)) motor neurons

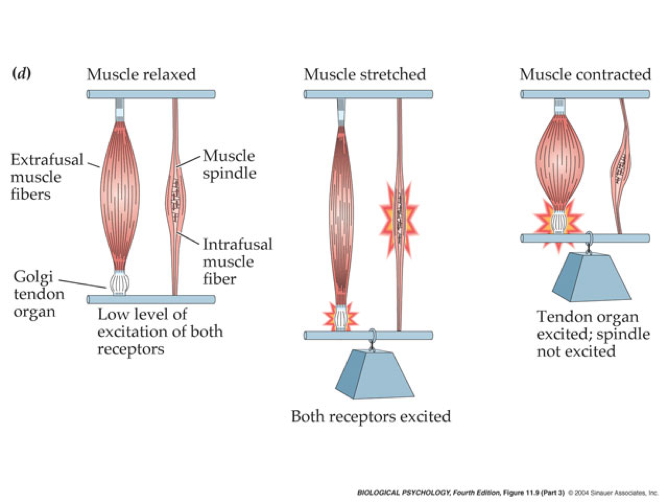

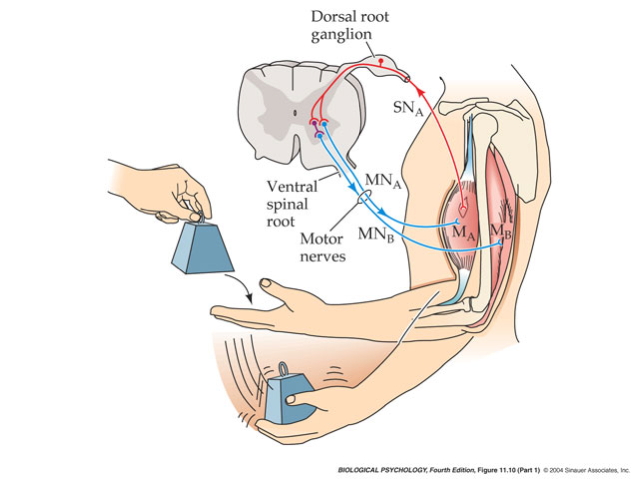

Monosynaptic stretch (myotatic) reflex

- Muscle stretched (length increases)

- Muscle spindle in intrafusal fiber activates

- Ia afferent sends signal to spinal cord

- Activates alpha (\(\alpha\)) motor neuron

- Muscle contracts, shortens length

- Gamma (\(\gamma\)) motor neuron fires to take up ‘slack’ in intrafusal fiber

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/HowtoBelay_3-571117903df78c3fa293859d.jpg)

Why doesn’t antagonist muscle respond?

- Polysynaptic inhibition of antagonist muscle

- Prevents/dampens tremor

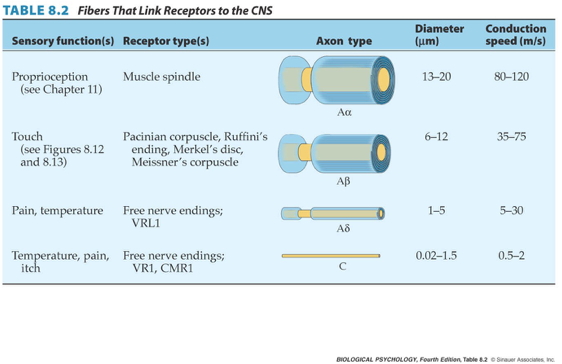

Speed of sensory information propagation

- Brain gets fast(est) propagating sensory info from spindles

What does motor cortex “code?”

Disorders of movement

- Parkinson’s

- Huntington’s

The Faces of Parkinson’s

- Slow, absent movement, resting tremor

- Cognitive deficits, depression

- DA Neurons in substantia nigra degenerate

- Treatments

- DA agonists

- DA agonists linked to impulse control disorders in ~1/7 patients (Ramirez-Zamora, Gee, Boyd, & Biller, 2016)

- Levodopa (L-Dopa), DA precursor

Huntington’s

- Formerly Huntington’s Chorea

- “Chorea” from Greek for “dance”

- “Dance-like” pattern of involuntary movements

- Cognitive decline

- Genetic + environmental influences

- Disturbance in striatum

- No effective treatment

- But progress in an animal model targeting abnormal protein products (Li et al., 2019)

Clinical trial focused on gene therapy

The big picture

- Control of movement determined by multiple sources

- Cerebral cortex + basal ganglia + cerebellum + spinal circuits

The “real” reason for brains

What does motor cortex activity encode?

- Muscle contractions?

- Movement trajectories?

- Representational vs. dynamical systems views

Figure 1. Schematic illustrating the focus of the representational perspective and of the dynamical systems perspective. The traditional perspective has concentrated on the representation or code employed by the motor cortex. For example, does the motor cortex (upper left panel) code muscle activity (red trace) or reach velocity (black trace)? Thus, the traditional perspective attempts to determine the output or controlled parameters of the motor cortex. The dynamical systems perspective focuses less on the output itself and more on how that output is created (upper right panel). It attempts to isolate the basic patterns (blue) from which the final output might be built. It further attempts to understand the dynamics that produced that set of patterns and the role of preparatory activity in creating the right set of patterns for a particular movement. The red trace indicates the activity of the deltoid versus time during a rightward reach (e.g., Churchland et al. 2012). The black trace is the hand velocity for that same reach; the black trace between the beginning and ending reach targets is the hand path. The light and dark blue traces (upper right) illustrate a potential dynamical basis set from which the red trace might be built.

Figure 2. Overview of experimental paradigm, behavioral measurements, muscle measurements, and neural measurements. (a) Illustration of the instructed-delay task. Monkeys sit in a primate chair ∼25 cm from a fronto-parallel display. A trial begins by fixating (eye) and touching (hand) a central target (red filled square) and holding for a few hundred milliseconds. A peripheral target (red open square) then appears, cuing the animal about where a movement must ultimately be made. After a randomized delay period (e.g., 0–1 s) a go cue is given (e.g., extinction of central fixation and touch targets) signaling that an arm movement to the peripheral target may begin. (b) Sample hand measurements and electromyographic (EMG) recordings for the same trial as in panel a. Top: Horizontal hand (black) and target (red) positions are plotted. For this experiment, the target jittered on first appearing and stabilized at the go cue. Bottom: Hand velocity superimposed on the voltage recorded from the medial deltoid. (c) Sample reach trajectories and end points in a center-out two-instructed-speed version of the instructed-delay task. Red and green traces/symbols correspond to instructed-fast and instructed-slow conditions. (d) Mean reaction time (RT) plotted versus delay-period duration. The line shows an exponential fit. (e) Examples of typical delay-period firing-rate responses in PMd. Mean ± Standard Error firing rates for four sample neurons are shown. Figure adapted from Churchland et al. (2006c).

Dynamical systems and state spaces

- Movement of the limbs and body

- Activity of the muscles

- Activity of neurons in the spinal cord

- Activity of neurons in the brain…

What does the cerebellum do?

- Predict future sensory states? (Ito, 2008)

Systems perspective

- Cognitive/affective states

- Nervous system states

- Muscle states

- Actions

- Consequences of actions on world states

- Sensory states

Fig. 2: The low-dimensional signature across cognitive tasks. a, The procedure used to partition tPC1 into unique phases: low (blue), rise (red), high (orange), and fall (light blue). b, Scatter plot comparing the loading of tPC1 (colored according to the partition defined in a) with a temporal stability measure (defined by the similarity of the BOLD response at adjacent time points); we observed a significant positive Pearson’s correlation (r=0.58) between |tPC1| and temporal stability (n=1,939 time points), providing heuristic evidence for attractor basins at the extremes of tPC1 engagement. c, A three-dimensional scatter plot comparing the first three tPCs; each node represents one time point (colored according to the phase of tPC1), with time implicitly unfolding across the embedding space (contiguous points connected by black line). d, The low-dimensional manifold traversed by the global brain state across the first three dimensions, with arrows depicting the direction of flow along the manifold. (Shine et al., 2019)

![[[@Nielsen2016-hs]](http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-013913)](https://www.annualreviews.org/na101/home/literatum/publisher/ar/journals/content/neuro/2016/neuro.2016.39.issue-1/annurev-neuro-070815-013913/20160711/images/large/ne390081.f1.jpeg)

![[[@Cantu2019-sz]](https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00951)](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/476718/fneur-10-00951-HTML/image_m/fneur-10-00951-g001.jpg)

![[[@Shenoy2013-zi]](http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150509)](https://www.annualreviews.org/na101/home/literatum/publisher/ar/journals/content/neuro/2013/neuro.2013.36.issue-1/annurev-neuro-062111-150509/20130626/images/large/ne360337.f1.jpeg)

![[[@Shenoy2013-zi]](http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150509)](https://www.annualreviews.org/na101/home/literatum/publisher/ar/journals/content/neuro/2013/neuro.2013.36.issue-1/annurev-neuro-062111-150509/20130626/images/large/ne360337.f2.jpeg)

![[[@Powers1973-zn]](http://www.pctresources.com/Other/Reviews/BCP_book.pdf)](img/powers-5.2.png)

![[[@Powers1973-zn]](http://www.pctresources.com/Other/Reviews/BCP_book.pdf)](img/powers-5.1.png)

![[[@Powers1973-zn]](http://www.pctresources.com/Other/Reviews/BCP_book.pdf)](img/powers-6.1.png)

![[[@Shine2019-lh]](http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0312-0)](https://media.springernature.com/lw685/springer-static/image/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41593-018-0312-0/MediaObjects/41593_2018_312_Fig2_HTML.png?as=webp)