flowchart LR A[world] --> B[mind] C[model] --> B B --> D[action]

Core Knowledge and a critique

2025-09-19

Department of Psychology

Prelude

Today’s topics

Background

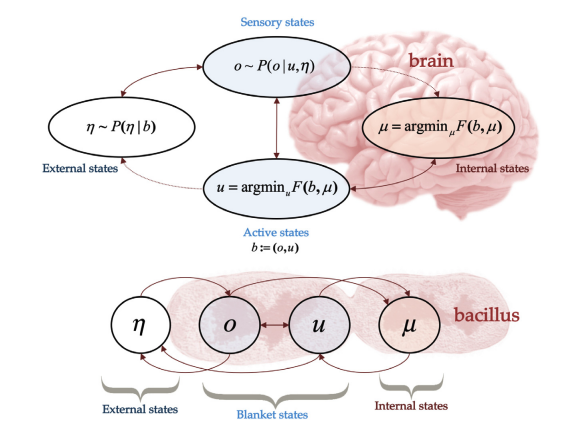

Active inference

…creatures use an internal forward (generative) model to predict their sensory input, which they use to infer the causes of these data.

– Da Costa et al. (2020)

Active inference

Da Costa et al. (2020) Figure 1

Active inference simplified

flowchart LR A[world] --> B[mind] C[pred_model] ---> B B --> C B --> D[action] D --> A D --> C

Why active inference is useful

- Predict the future (sensory or internal states)

- Produce effective actions

- Detect novelty (sensation \(\neq\) prediction)

Ecological approach

- James J. Gibson

Ecological approach

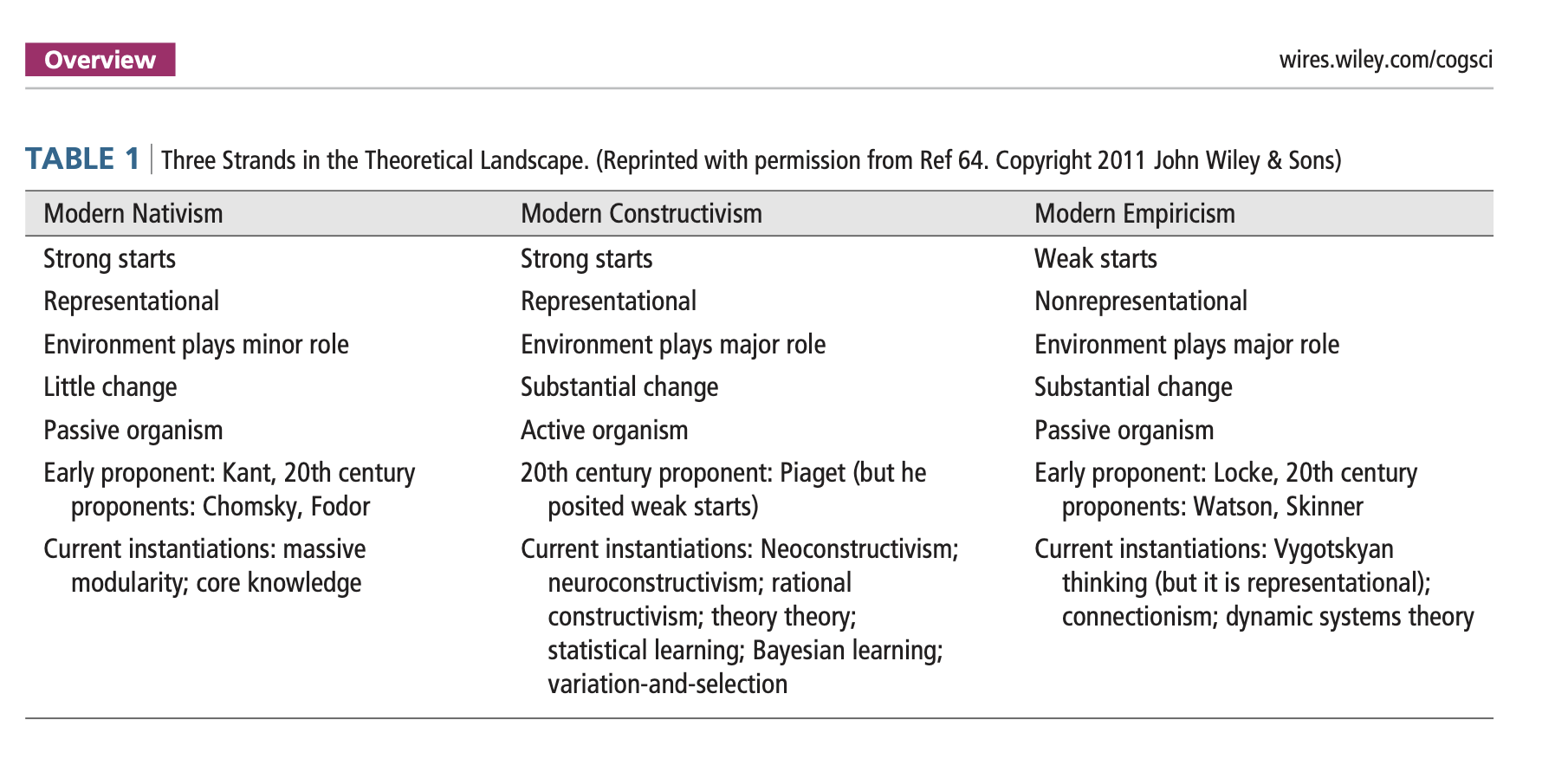

Newcombe (2013) Table 1

- Biologically relevant properties of environment useful for meaningful action (affordances) are perceived directly

Core knowledge

Domains

- (Inanimate) Objects

- Agents and actions

- Number

- Geometry

What core knowledge affords

- Interpreting/understanding perceptual information

- Predicting future events

- Acting under uncertainty

Moving beyond nurture vs. nature

On one view, the human mind is a flexible and adaptable mechanism for discovering regularities in experience: a single learning system that copes with all the diversity of life.

On the competing view, the human mind is a collection of special-purpose mechanisms, each shaped by evolution to perform a particular function.

– Spelke & Kinzler (2007)

Moving beyond nurture vs. nature

…both these views are false: humans are endowed neither with a single, general-purpose learning system nor with myriad special-purpose systems and predispositions. Instead, we believe that humans are endowed with a small number of separable systems of core knowledge. New, flexible skills and belief systems build on these core foundations.

– Spelke & Kinzler (2007)

Developmental systems critique

Origins of core knowledge

developmental scientists should no longer embrace ‘endowments,’ ‘primitives,’ ‘core knowledge,’ ‘essences’ (Gelman, 2003), or other static concepts that devalue developmental process. After all, ‘endowments’ are bestowed, not developed.

– Spencer, Blumberg, et al. (2009)

Evolution and development

the fact that organisms evolved does not remove the need to explain developmental process, because brain and behavior are shaped through development, not programmed before development.

– Spencer, Blumberg, et al. (2009)

Methodology and style

…nativists routinely extrapolate well beyond the data, making bold claims about time points not directly under investigation…

We contend that more satisfying accounts can be found through rigorous developmental analyses that embrace process, complexity, and evolutionary history.

– Spencer, Blumberg, et al. (2009)

In defense of core knowledge

This commentary argues that the dialogue between nativism and empiricism is a rich source of insight into the nature and development of human knowledge.

– Spelke & Kinzler (2009)

What’s innate?

Innate means not learned, and so claims of innateness and learning are mutually dependent. The second reason is conceptual: Any learning mechanism necessarily requires unlearned abilities for detecting and analyzing inputs and for drawing inferences, and so claims of learning inevitably presuppose a set of innate capacities.

– Spelke & Kinzler (2009)

Core knowledge vs. developmental systems

…does a perspective promote understanding of currently known phenomena and thinking about current problems? Second, does it foster new lines of research?

We argue here that the nativist–empiricist dialogue scores high on both measures. In contrast, Spencer et al. provide no evidence that their developmental process approach passes either test.

– Spelke & Kinzler (2009)

Core knowledge vs. developmental systems

The empirical tools of psychology and cognitive neuroscience allow us to test specific claims of innateness and learning with a vast array of methods, and to target levels of analysis from molecules to mind and action.

– Spelke & Kinzler (2009)

Stepping back

What is this debate about?

- Is “innate” a useful construct? (Spencer, Blumberg, et al., 2009; Spencer, Samuelson, et al., 2009)

- Are we debating or in dialogue? (Spelke & Kinzler, 2009; Spencer, Blumberg, et al., 2009; Spencer, Samuelson, et al., 2009)

- Does every theory need primitives and processes? (Landau, 2009)

- What constitutes experience? (Spencer, Blumberg, et al., 2009; Spencer, Samuelson, et al., 2009)

- Is learning \(\neq\) innate

What is the debate about?

- How to account for the speed, consistency, etc. of cognitive development (Spelke & Kinzler, 2009)

- How does (and should) evidence from neuroscience inform these questions (Spelke & Kinzler, 2009; Spencer, Blumberg, et al., 2009; Spencer, Samuelson, et al., 2009)

- How does (and should) evolutionary theory shape developmental theory? (Spelke & Kinzler, 2007; Spencer, Blumberg, et al., 2009)

- How computational/statistical perspectives shape developmental theory? (Spelke & Kinzler, 2007; Spencer, Blumberg, et al., 2009)

What about the domains themselves?

- Objects vs. agents?

- Geometry: Layout vs. landmarks?

Knowledge

- Knowing that (semantic) vs. knowing how (procedural)

Peripheral vs. central origins

It is often proposed that human psychological functions develop from the periphery inward: Perception and action develop on the basis of sensory and motor experience, and reasoning develops on the basis of perception and action.

– Spelke, Breinlinger, Macomber, & Jacobson (1992)

Peripheral vs. central origins

…a number of psychologists have proposed that there are crucial differences between perceptual and motor processes on the one hand and central cognitive processes on the other..

– Spelke et al. (1992)

Peripheral vs. central origins

Whereas perception and action depend on a collection of relatively autonomous mechanisms that develop rapidly under internal constraints, thinking depends on processes that operate and develop more slowly, without the internal constraints that a modular architecture would impose.

– Spelke et al. (1992)

Peripheral vs. central origins

We will explore a different view of cognitive development, traceable in part from Descartes (1637/1956) and Kant (1929) to Chomsky (1975). Cognition develops from its own foundations, rather than from a foundation of perception and action.

– Spelke et al. (1992)

Active representations and core knowledge

…young infants are capable of reasoning: They can represent states of the world that they no longer perceive. By operating on these representations, infants come to know about states of the world that they never perceived.

– Spelke et al. (1992)

Active representations and core knowledge

young infants’ reasoning accords with principles at the center of mature, commonsense conceptions.

– Spelke et al. (1992)

Next time…

- Nativism and Core Knowledge: Deep dive

- Student Presentation C: How does changing the task inform on the underlying construct(s) about physical knowledge? (Presenter: Carlos Almeida; Discussant: Yeonjin Kim)

- Student Presentation D: Rich interpretation of group differences in infant looking-time paradigms: How rich is dangerous? Necessary? Productive? (Presenter: Suzy Su; Discussant: Makenna Luzeknski)

Resources

About

This talk was produced using Quarto, using the RStudio Integrated Development Environment (IDE), version 2025.5.1.513.

The source files are in R and R Markdown, then rendered to HTML using the revealJS framework. The HTML slides are hosted in a GitHub repo and served by GitHub pages: https://psu-psychology.github.io/psy-548-fall/