2023-08-30 Wed

Scientific norms and counter-norms

Overview

Announcements

- Due Friday

Today

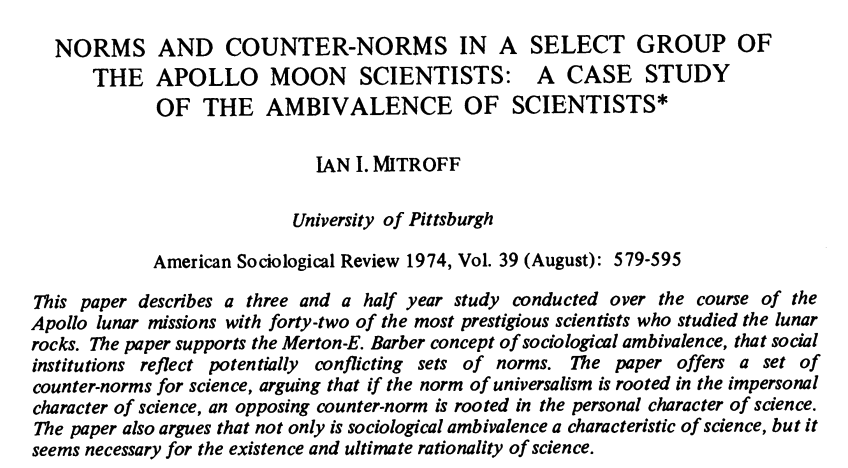

Scientific norms and counter-norms

- Read

- Assignment

- Complete (anonymous) survey on scientific norms and counter-norms. No write-up.

Scientific norms and counter-norms

What is science, really?

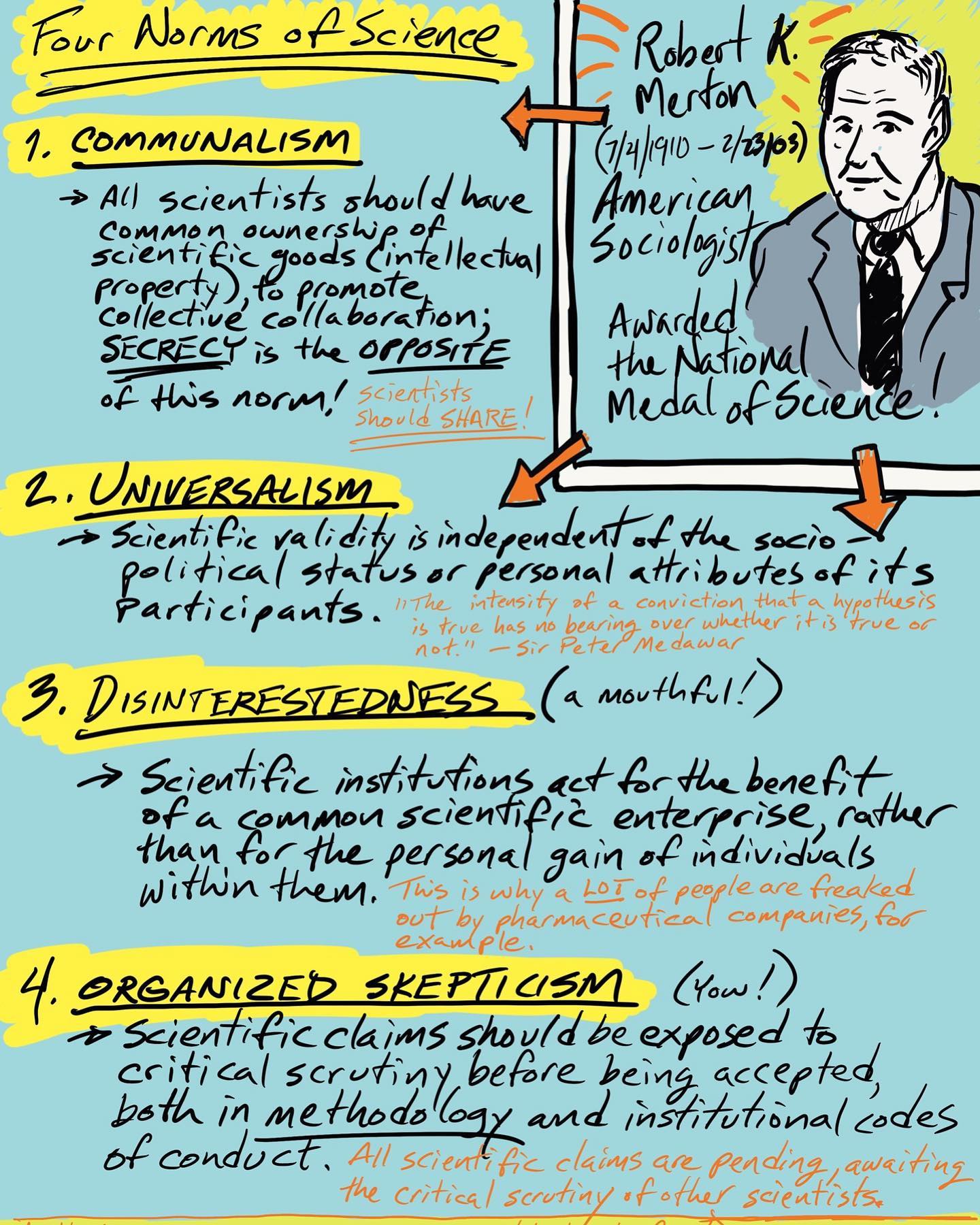

Robert Merton

- a stock of accumulated knowledge (facts & findings)

- a set of characteristic methods

- a set of cultural values

Questions

- Why is it important to talk about and illuminate the cultural values that are part of scientific research?

- How important are these values relative to facts and findings or methods?

Difficult as the notion may appear to those reared in a culture that grants science a prominent if not a commanding place in the scheme of things, it is evident that science is not immune from attack, restraint, and repression. Writing a little while ago, Veblen could observe that the faith of western culture in science was unbounded, unquestioned, unrivaled.

…The revolt from science which then appeared so improbable as to concern only the timid academician who would ponder all contingencies, however remote, has now been forced upon the attention of scientist and layman alike. Local contagions of anti-intellectualism threaten to become epidemic.

Questions

- What’s the difference between principled skepticism about specific scientific claims and “anti-intellectualism”?

- Do you agree with Merton that “Local contagions of anti-intellectualism threaten to become epidemic.”?

The ethos of science

The mores of science possess a methodologic rationale but they are binding, not only because they are procedurally efficient, but because they are believed right and good.

Question

- How are scientific methods efficient?

Robert Merton

“Communism”

- Often called “communalism” today

“Communism” in the nontechnical and extended sense of common ownership of goods…The substantive findings of science are a product of a social collaboration and are assigned to the community…Property rights in sciences are whittled down to a bare minimum by the rationale of the scientific ethic.

The institutional conception of science as part of the public domain is linked with the imperative for communication of scientific findings. Secrecy is the antithesis of this norm; full and open communication is its enactment.

- Henry Cavendish was known for not publishing much of his work.

Universalism

To restrict scientific careers on grounds other than lack of competence is to prejudice the furtherance of knowledge.

Disinterestedness

The virtual absence of fraud in the annals of science, which appears exceptional when compared with the record of other spheres of activity, has at times been attributed to the personal qualities of scientists…There is, in fact, no satisfactory evidence that such is the case…

…a more plausible explanation may be found in certain characteristcs of science itself…the activities of scientists are subject to rigorous policing, to a degree perhaps unparalleled in any other field of activity.

It is probable that the reputability of science and its lofty ethical status in the estimate of the layman is in no small measure due to technological achievements…the laity is often in no position to distinguish spurious from genuine claims…The presumably scientific pronouncements of totalitarian spokesmen are for the uninstructed laity of the same order as newspaper reports on an expanding universe or wave mechanics.

Organized Skepticism

…is variously interrelated with other elements of the scientific ethos. It is both a methodological and institutional mandate.

The scientific investigator does not preserve the cleavage between the sacred and the profane, between that which requires uncritical respect and that which can be objectively analyzed.

Mnemonic: C-U-D-OS

Hogwash!

…the personal character of science infuses its entire structure. The testing and validating of scientific ideas is as governed by the deep personal character of science as the initial discovery of the ideas…Polyani (1958) argues that not only is this the case, but it ought to be the case. That is, science outght to be personal to its core.

…what the body of scientists thought about their fellow scientists. Who were perceived as most committed to their pet hypotheses? What did they think of such behavior? What did the scientists think of the abstract idea of commitment [to a pet hypothesis] itself…

All the interviews exhibit high affective content. They document the often fierce, sometimes bitter, competitive races for discovery and the intense emotions which permeate the doing of science.

The term “commitment” was used in three distinct (but related) senses. The first expresssed the notion of intellectual commitment, that is that scientific observerations were theory-laden…The second sense expressed the notion of affective commitment…The third sense expressed the notion that the entire process of science demanded deep personal commitment.

Norms vs. Counter-norms

| Norm | Counternorm |

|---|---|

| Faith in the moral virtue of rationality (Barber, 1952). | Faith in the moral virtue of rationality and nonrationality (cf., Tart, 1972). |

| Emotional neutrality as an instrumental condition for the achievement of rationality (Barber, 1952). | Emotional commitment as an instrumental condition for the achievement of rationality. |

| Norm | Counternorm |

|---|---|

| Universalism: The acceptance or rejection of claims entering the list of science is not to depend on the personal or social attributes of their protagonist; his race, nationality, religion, class and personal qualities are as such irrelevant. | Particularism: “The acceptance or rejection of claims entering the list of science is to a large extent a function of who makes the claim” (Boguslaw, 1968:59) |

| Norm | Counternorm |

|---|---|

| Communism: “Property rights are reduced to the absolute minimum of credit for priority of discovery” (Barber, 1952:130). “Secrecy is the antithesis’ of this norm; full and open communication [of scientific results] its enactment” (Merton, 1949:611). | Solitariness (or, “Miserism” [Boguslaw, 1968:59]): Property rights are expanded to include protective control over the disposition of one’s discoveries; secrecy thus becomes a necessary moral act. |

| Norm | Counternorm |

|---|---|

| Disinterestedness: “Scientists are expected by their peers to achieve the self-interest they have in work–satisfaction and in prestige through serving the [scientific] community interest directly” (Barber, 1952:132). | Interestedness: Scientists are expected by their close colleagues to achieve the self-interest they have in work-satisfaction and in prestige through serving their special communities of interest, e.g., their invisible college (Boguslaw, 1968:59; Mitroff, 1974b) |

Science as a human activity

- Humans are…

- flawed

- often illogical

- emotional AND intellectual

- biased

- have blind spots

- By what means can we mitigate or overcome these?

Next time

Work session: Norms and counter-norms

Resources

Show recommendation

Alternative history depicting what might have happened had the Soviets beaten the United States to the Moon in the summer of 1969.