2023-09-20 Wed

What R we talking about?

Overview

Announcements

Last time…

Today

What R we talking about?

- Read & Discuss

- (Fidler & Wilcox, 2021)

- (Skim) (Nosek et al., 2022) and (Goodman, Fanelli, & Ioannidis, 2016)

- Small group discussion and reports

Discussing the “R’s”

Fidler, F. & Wilcox, J. (2021). Reproducibility of Scientific Results. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/scientific-reproducibility/

Nosek, B. A., Hardwicke, T. E., Moshontz, H., Allard, A., Corker, K. S., Dreber, A., Fidler, F., Hilgard, J., Kline Struhl, M., Nuijten, M. B., Rohrer, J. M., Romero, F., Scheel, A. M., Scherer, L. D., Schönbrodt, F. D. & Vazire, S. (2022). Replicability, robustness, and reproducibility in psychological science. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(2022), 719–748. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-114157

Goodman, S. N., Fanelli, D. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2016). What does research reproducibility mean? Science Translational Medicine, 8(341), 341ps12–ps341ps12. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf5027

(Fidler & Wilcox, 2021)

Replicability

“When describing a study as “replicable”, people could have in mind either of at least two different things. The first is that the study is replicable in principle the sense that it can be carried out again, particularly when its methods, procedures and analysis are described in a sufficiently detailed and transparent way. The second is that the study is replicable in that sense that it can be carried out again and, when this happens, the replication study will successfully produce the same or sufficiently similar results as the original. A study may be replicable in the former sense but not in the second sense: one might be able to replicate the methods, procedures and analysis of a study, but fail to successfully replicate the results of the original study. Similarly, when people talk of a “replication”, they could also have in mind two different things: the replication of the methods, procedures and analysis of a study (irrespective of the results) or, alternatively, the replication of such methods, procedures and analysis as well as the results.”

Replication in different disciplines

- (Gómez, Juristo, & Vegas, 2010) identify 79 types across 18 disciplines, see (Fidler & Wilcox, 2021)

- Things that vary:

- site or spatial location

- experimenters

- apparatus

- operationalisations or measurement of variables

- population properties

Functions of replication

(Fidler & Wilcox, 2021) discussing Schmidt (2009)

Function 1. Controlling for sampling error—that is, to verify that previous results in a sample were not obtained purely by chance outcomes which paint a distorted picture of reality

- Function 2. Controlling for artifacts (internal validity)—that is, ensuring that experimental results are a proper test of the hypothesis (i.e., have internal validity) and do not reflect unintended flaws in the study design (such as when a measurement result is, say, an artifact of a faulty thermometer rather than an actual change in a substance’s temperature)

- Function 3. Controlling for fraud,

- Function 4. Enabling generalizability,

- Function 5. Enabling verification of the underlying hypothesis.

What to manipulate to achieve these…

(Fidler & Wilcox, 2021) discussing (Schmidt, 2009)

Class 1. Information conveyed to participants (for example, their task instructions).

- Class 2. Context and background. This is a large class of variables, and it includes: participant characteristics (e.g., age, gender, specific history); the physical setting of the research; characteristics of the experimenter; incidental characteristics of materials (e.g., type of font, colour of the room),

- Class 3. Participant recruitment, including selection of participants and allocation to conditions (such as experimental or control conditions),

- Class 4. Dependent variable measures (or in Schmidt’s terms “procedures for the constitution of the dependent variable”, 2009: 93)

(Goodman et al., 2016)

“The language and conceptual framework of ‘research reproducibility’ are nonstandard and unsettled across the sciences. In this Perspective, we review an array of explicit and implicit definitions of reproducibility and related terminology, and discuss how to avoid potential misunderstandings when these terms are used as a surrogate for ‘truth’.”

(Figure 1 from Goodman et al., 2016)

(Figure 1 caption from Goodman et al., 2016)

Number of publications recorded in Scopus that have, in the title or abstract, at least one of the following expressions: research reproducibility, reproducibility of research, reproducibility of results, results reproducibility, reproducibility of study, study reproducibility, reproducible research, reproducible finding, or reproducible result. Papers are classified by discipline on the basis of the journal, following an adaptation and expansion of Thomson Reuters’ Essential Science Indicators classification system. Journals not included in the latter database were hand-classified on the basis of their name. The subplot reports the percentage over the total number of records for each discipline, in the last 2 years of the series. Disciplines legend: MA, mathematics; CS, computer sciences; EN, engineering; SP, space science; PH, physics; CH, chemistry; BB, biology and biochemistry; MB, molecular biology; MI, microbiology; PT, pharmacology and toxicology; CM, clinical medicine; NB, neurobiology and behavior; PA, plant and animal sciences; EE, environment and ecology; AG, agricultural sciences; EB, economics and business; PP, psychology and psychiatry; SO, social sciences, general; AH, arts and humanities; MU, multidisciplinary. The time series was truncated at 2014.

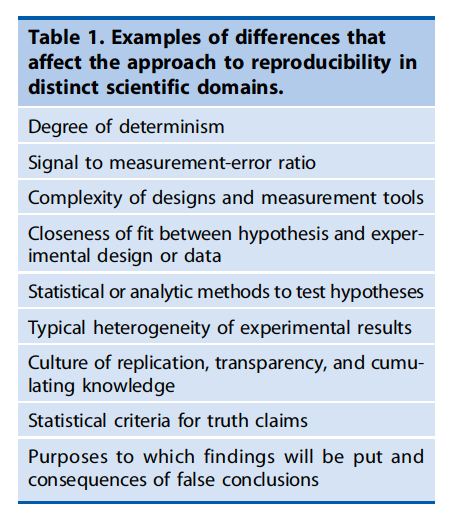

Differences among scientific fields/domains

Table 1 from Goodman et al. (2016)

Reproducibility

“Although the importance of multiple studies corroborating a given result is acknowledged in virtually all of the sciences (Fig. 1), the modern use of “reproducible research” was originally applied not to corroboration, but to transparency, with application in the computational sciences. Computer scientist Jon Claerbout coined the term and associated it with a software platform and set of procedures that permit the reader of a paper to see the entire processing trail from the raw data and code to figures and tables (4).”

(Goodman et al., 2016)

“According to a U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) subcommittee on replicability in science (9), ‘reproducibility refers to the ability of a researcher to duplicate the results of a prior study using the same materials as were used by the original investigator. That is, a second researcher might use the same raw data to build the same analysis files and implement the same statistical analysis in an attempt to yield the same results…Reproducibility is a minimum necessary condition for a finding to be believable and informative.’”

“…Reproducibility refers to testing the reliability of a prior finding using the same data and the same analysis strategy (Natl. Acad. Sci. Eng. Med. 2019)…In principle, all reported evidence should be reproducible. If someone applies the same analysis to the same data, the same result should occur…”

Methods reproducibility

- Goodman et al. (2016)

- Enough details about materials & methods recorded (& reported), so…

- Same results with same materials & methods

(Goodman et al., 2016, fig. 1)

“In the biomedical sciences, this means, at minimum, a detailed study protocol, a description of measurement procedures, the data gathered, the data used for analysis with descriptive metadata, the analysis software and code, and the final analytical results. In laboratory science, how key reagents and biological materials were created or obtained can be critical. In theory, these requirements are clear, but in practice, the level of procedural detail needed to describe a study as “methodologically reproducible” does not have consensus.”

Results reproducibility

- Goodman et al. (2016)

- Same results from “independent study whose procedures are as closely matched to the original experiment as possible.”

Inferential reproducibility

- Goodman et al. (2016)

- Same inferences from one or more studies or reanalyses

- “Inferential reproducibility is not identical to results reproducibility or to methods reproducibility, because scientists might draw the same conclusions from different sets of studies and data or could draw different conclusions from the same original data, sometimes even if they agree on the analytical results.”

(Nosek et al., 2022)

Themes

- replication

- reproducibility

- robustness

Reproducibility

“In principle, all reported evidence should be reproducible. If someone applies the same analysis to the same data, the same result should occur. Reproducibility tests can fail for two reasons. A process reproducibility failure occurs when the original analysis cannot be repeated because of the unavailability of data, code, information needed to recreate the code, or necessary software or tools. An outcome reproducibility failure occurs when the reanalysis obtains a different result than the one reported originally. This can occur because of an error in either the original or the reproduction study.”

Robustness

“Some evidence is robust across reasonable variations in analysis, and some evidence is fragile, meaning that support for the finding is contingent on specific decisions such as which observations are excluded and which covariates are included….Robustness refers to testing the reliability of a prior finding using the same data and a different analysis strategy…”

- “Many analysts”: (Botvinik-Nezer et al., 2020; Silberzahn et al., 2018)

Replicability

The credibility of a scientific finding depends in part on the replicability of the supporting evidence…Replication seems straightforward—do the same study again and see if the same outcome recurs—but it is not easy to determine what counts as the same study or same outcome.

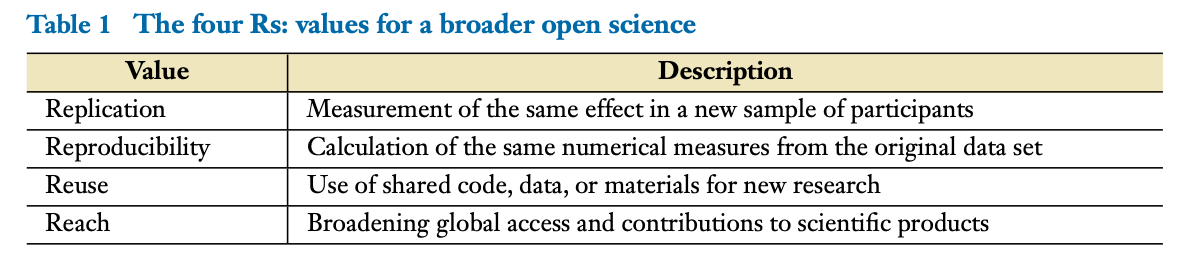

Two additional “R’s”

Table 1 from Gennetian, Frank, & Tamis-LeMonda (2022)

- Reuse

- Reach

Your turn

What do you think?

- Does “repetition” == “reproduction” == “replication”?

What do you think?

- Does replication success imply robustness?

- Or, does replication failure or difficulty imply a finding is false?

What do you think?

Is exact replication even possible?

“…every study is unique; the evidence it produces applies only to a context that will never occur again (Gergen 1973)” (Nosek et al., 2022)

What do you think?

- What other domains (outside of scientific research) emphasize repetition, replication, or reproduction?

- What lessons might we learn from them?

What do you think?

- What kind of replicability/reproducibility should we expect from psychology findings, especially journal articles?

What do you think?

- What 2 or 3 things would you like to see research psychologists or psychology journals implement to improve the “R’s”?

Next time

Work session: Scientific integrity

Resources

References

PSYCH 490.009: 2023-09-20 Wednesday