[1] "id" "author1field" "author2field"

[4] "author3field" "discipline" "discipline2"

[7] "POL" "PSY" "SOC"

[10] "OTHER" "year" "fieldingperiod1stday"

[13] "age_months" "age_day" "age_year"

[16] "timetopublish" "iv_coder1" "iv_coder2"

[19] "disagreement" "IV_all" "IV"

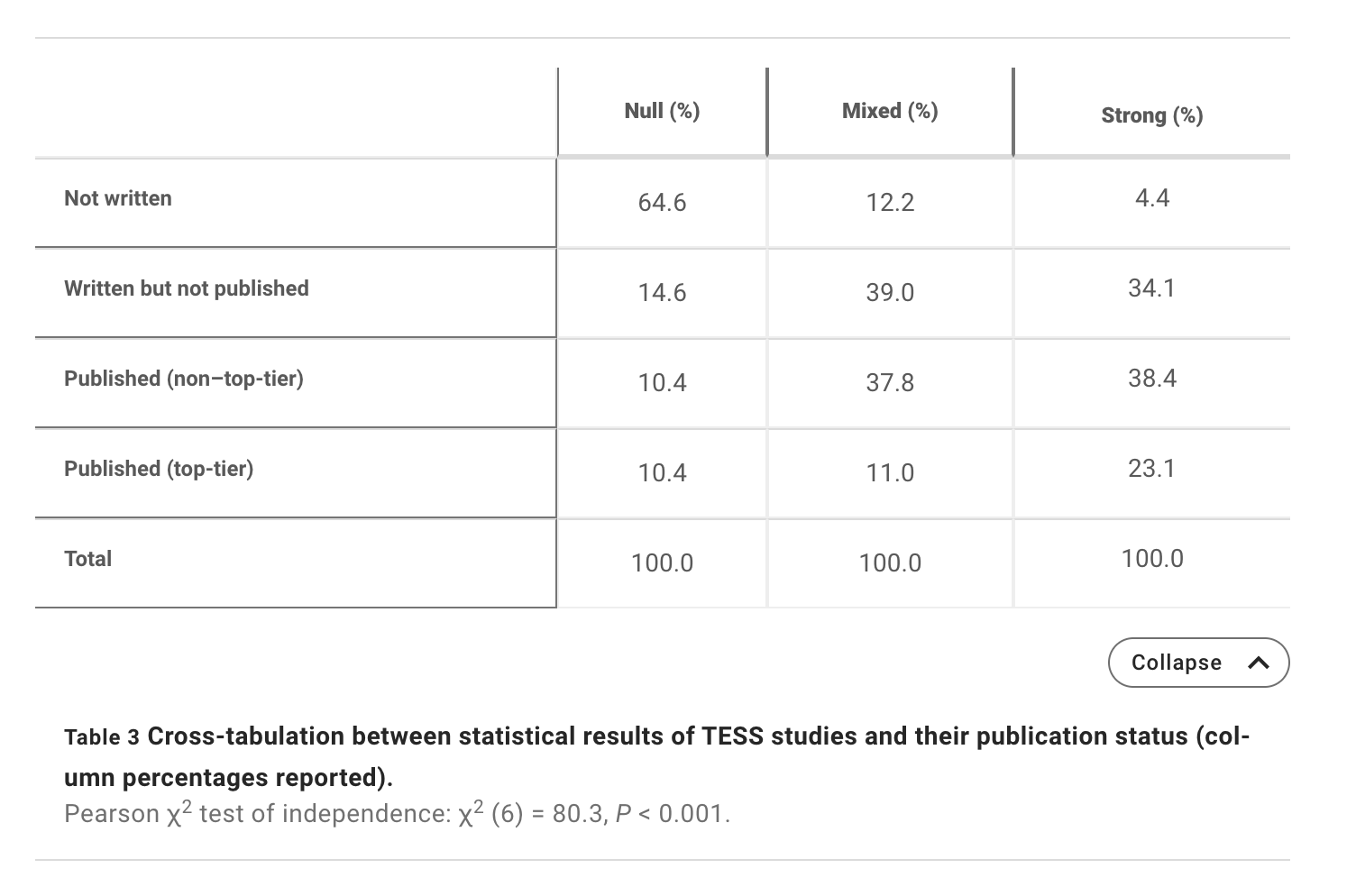

[22] "strong" "mixed" "null"

[25] "DV" "DV_all" "DV_tri"

[28] "DV_book_separate" "DV_book_unpub" "DV_book_nontop"

[31] "DV_book_top" "journal" "journal_field"

[34] "insample" "pubyear" "pub"

[37] "anyresults" "written" "max_h_current"

[40] "max_pub_attime" "why_excluded"

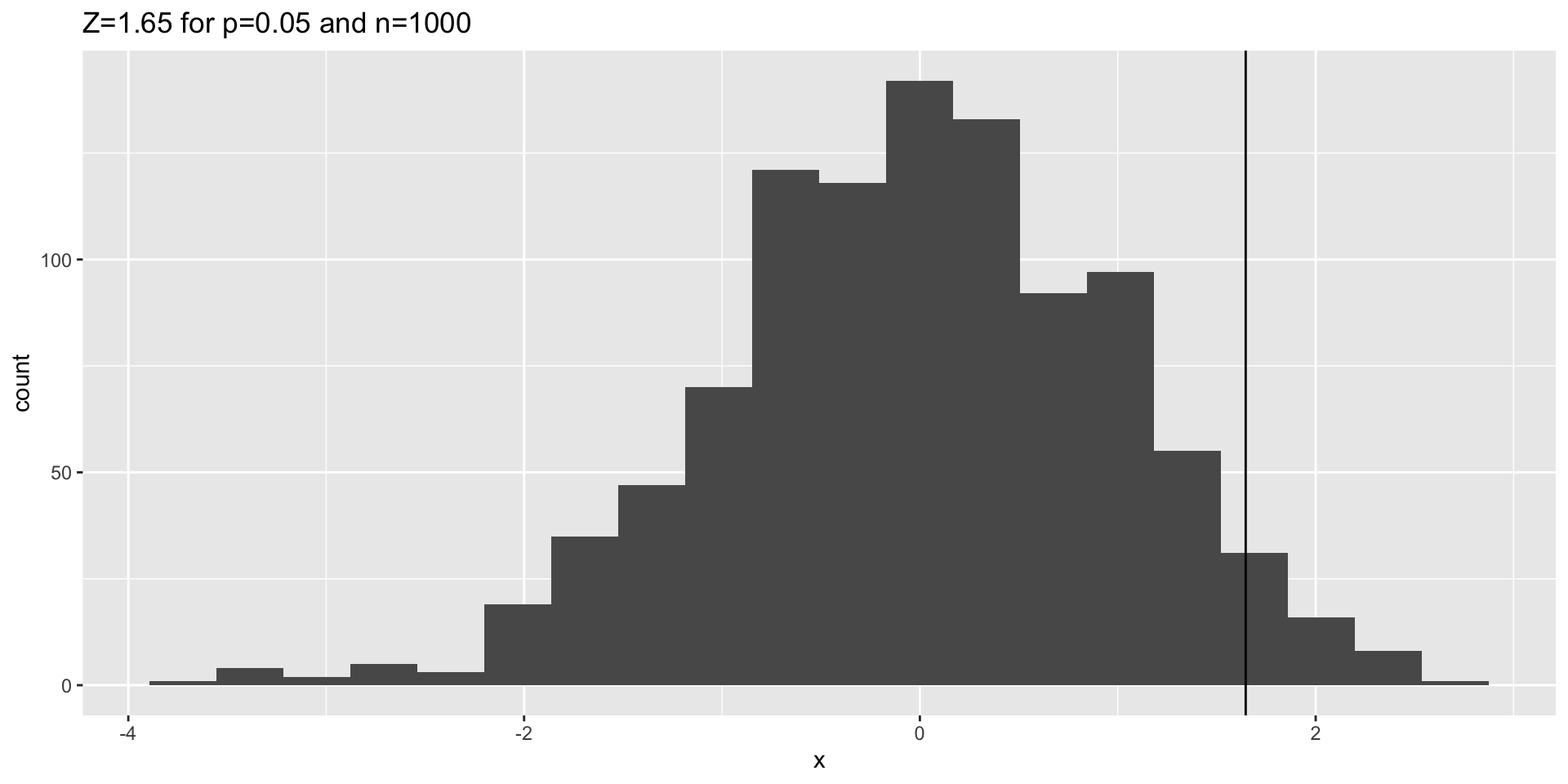

Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction

data: bounds

X-squared = 70.503, df = 1, p-value < 2.2e-16quartz_off_screen

2