Priming effect: Original study

2024-09-23 Mon

Overview

Announcements

- Due Friday, September 27

Last time…

Earp et al. (2014)

- How did the authors manipulate participants’ “need to cleanse”?

- How did they measure participants’ “need to cleanse”?

- Which groups of participants showed behavioral differences between the ‘ethical’ and ‘unethical’ manipulation?

- What do the results mean about the claims made by Zhong & Liljenquist (2006)?

Today

Priming effect: Original study

Bargh et al. (1996)

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M. & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype-activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.230.

Important

- Abstract-only publicly available, PDF $14.95.

- Web (HTML) and PDF versions available via PSU Libraries.

Abstract

Previous research has shown that trait concepts and stereotypes become active automatically in the presence of relevant behavior or stereotyped-group features. Through the use of the same priming procedures as in previous impression formation research,…

…Experiment 1 showed that participants whose concept of rudeness was primed interrupted the experimenter more quickly and frequently than did participants primed with polite-related stimuli.

…In Experiment 2, participants for whom an elderly stereotype was primed walked more slowly down the hallway when leaving the experiment than did control participants, consistent with the content of that stereotype.

…In Experiment 3, participants for whom the African American stereotype was primed subliminally reacted with more hostility to a vexatious request of the experimenter.

Implications of this automatic behavior priming effect for self-fulfilling prophecies are discussed, as is whether social behavior is necessarily mediated by conscious choice processes.

Unpacking Bargh et al. (1996)

- Experiment 1

- Participants: Who were they, how many, what characteristics?

- Materials & Procedure: What did participants do?

- Measure(s): What did researcher(s) measure?

- Prediction(s): What did researchers predict? What sort of data picture would that yield?

- Experiment 2

- Participants: Who were they, how many, what characteristics?

- Materials & Procedure: What did participants do?

- Measure(s): What did researcher(s) measure?

- Prediction(s): What did researchers predict? What sort of data picture would that yield?

Important

Work with students in your row to answer the questions.

You have 15 mins.

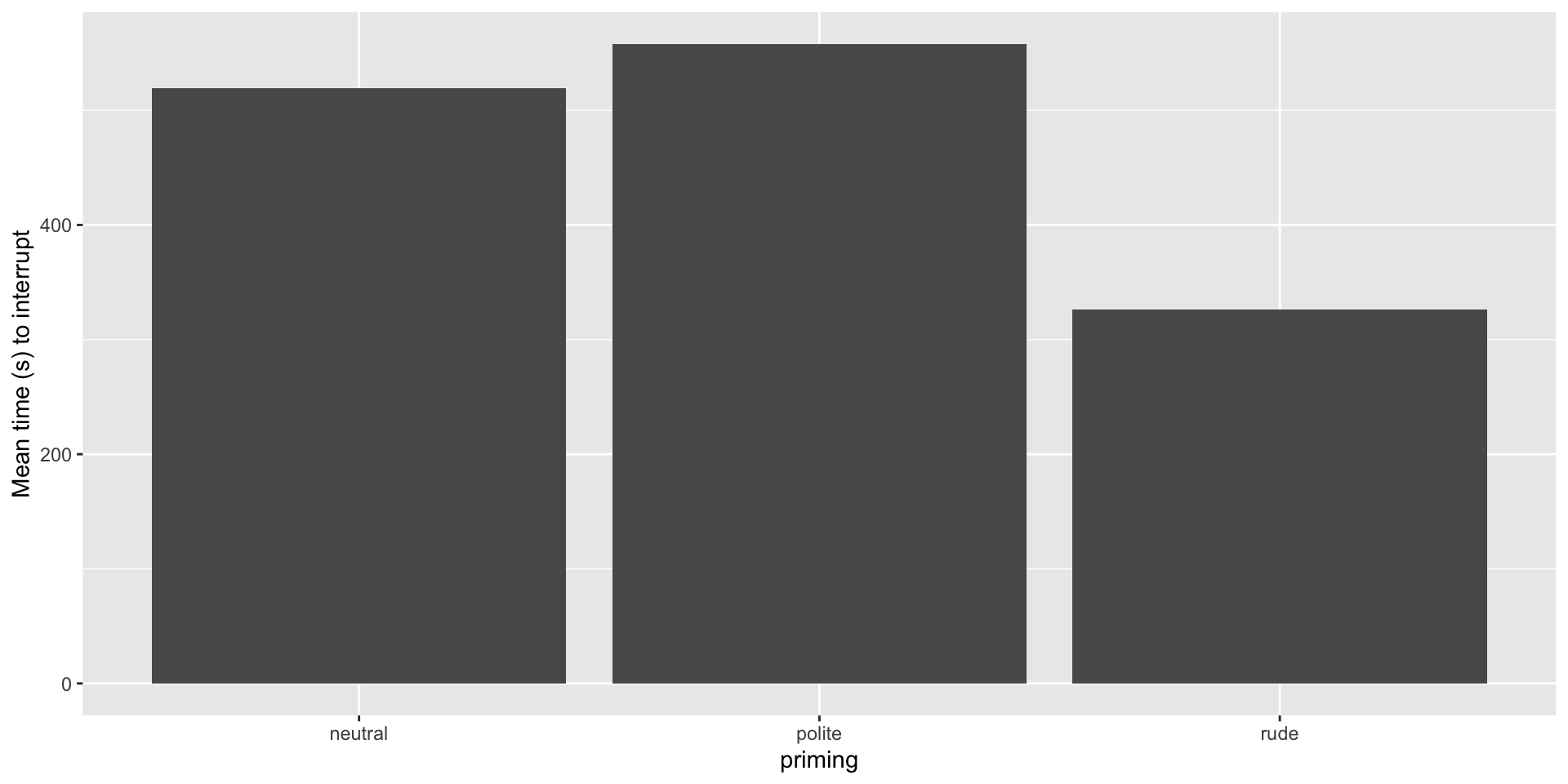

(Bargh et al., 1996 Experiment 1) results

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of these data, with priming condition as the single factor, revealed a significant main effect, F(2, 33) = 5.76, p=.008. Participants in the rude priming condition interrupted significantly faster (M = 326 s) than did participants in the neutral (M = 519 s) or polite (M = 558 s) priming conditions.

Figure 1: Visualization of Bargh et al. (1996) Experiment 1 RT results. Note: This figure was not in the original paper.

Important

The F test here evaluates whether all of the mean RTs are equal.

Within the significant main effect, simple t tests revealed that the rude prime condition mean was significantly shorter than each of the other two means (both ps < .04), which were not reliably different from one another (t < 1).

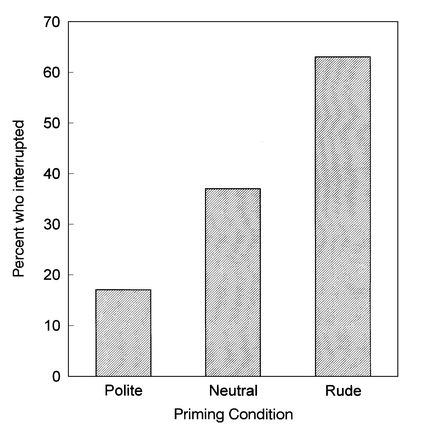

Although this result supports our hypothesis that social interaction behavior can be primed, the time-to-interruption distribution varied considerably from normality. Fully 21 of the 34 participants did not interrupt at all in the 10 min available to them, so that the time variable suffered from a severe ceiling effect. Thus, we reanalyzed the data in terms of the percentage of participants in each priming condition who interrupted at all during the 10-min period.

Figure 1 from (Bargh et al., 1996)

Important

How long did the participants take to complete the scrambled-sentence task?

Could there be any relationship between how long they took on the scrambled-sentence task and their subsequent behavior?

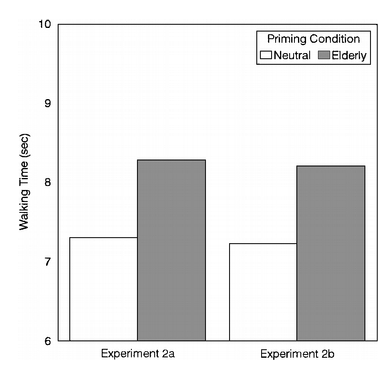

Experiments 2a and 2b

Participants were instructed to work on a scrambled-sentence task as part of a language proficiency experiment. The scrambled-sentence task contained words relevant to the elderly stereotype in the elderly priming condition, but all references to slowness, which is a quality stereotypically associated with elderly people, were excluded.

- Priming words

- “Elderly” condition: worried, Florida, old, lonely, grey, selfishly, careful, sentimental, wise, stubborn, courteous, bingo, withdraw, forgetful, retired, wrinkle, rigid, traditional, bitter, obedient, conservative, knits, dependent, ancient, helpless, gullible, cautious, and alone

- Neutral condition: thirsty, clean, private, ..

- Experiments 2a and 2b had 30 participants/study.

Waiting until the participant had gathered all of his or her belongings, the experimenter told the participant that the elevator was down the hall and thanked him or her for participating.

Using a hidden stopwatch, a confederate of the experimenter, who was sitting in a chair apparently waiting to talk to a professor in a nearby office, recorded the amount of time in seconds that the participant spent walking a length of the corridor starting from the doorway of the experimental room and ending at a broad strip of silver carpet tape on the floor 9.75 m away.

Participants in the elderly priming condition (M = 8.28 s) had a slower walking speed compared to participants in the neutral priming condition (M = 7.30 s), t (28) = 2.86, p < .01, as predicted.

Figure 2: Figure 2 from Bargh et al. (1996)

What do you notice about Figure 2?

Awareness check study

The crucial factor in concluding that these results show automatic effects on behavior derives from the perceiver’s lack of awareness of the influence of the words. Previous research (see review in Bargh, 1992) has indicated that it is not whether the primes are presented supraliminally or subliminally, but whether the individual is aware of the potential influence of the prime that is critical;…

diametrically opposite effects on judgments are obtained if the participant is aware versus not aware of a possible influence by the priming stimuli (see Lombardi, Higgins, & Bargh, 1987; Strack & Hannover, 1996). We conducted a subsequent study to explicitly test whether the participants were aware of the potential influence of the scrambled-sentence task.

Our conclusions in terms of automatic social behavior depend on the participants’ not being aware of this influence.

Method

Nineteen male and female undergraduate students at New York University participated in the experiment to partially fulfill course credit. On arrival at the laboratory waiting room, participants were randomly assigned to either the elderly stereotype priming condition or the neutral priming condition.

Participants took part in the experiment one at a time. They were informed that the purpose of the study was to investigate language proficiency and that they would complete a scrambled-sentence task. Participants were randomly administered either the version of the task containing words relevant to the elderly stereotype or the neutral version containing no stereotype-relevant words.

Immediately after completion of the task, participants were asked to complete a version of the contingency awareness funnel debriefing, modeled after Page (1969). This contingency awareness debriefing contained items concerning the purpose of the study, whether the participant had suspected that the purpose of the experiment was different from what the experimenter had explained…

whether the words had any relation to each other, what possible ways the words could have influenced their behavior, whether the participants could predict the direction of an influence…

if the experimenter had intended one, what the words in the scrambled-sentence task could have related to (if anything), and if the participant had suspected or had noticed any relation between the scrambled-sentence task and the concept of age. Afterward, the experimenter explained the hypotheses to the participants and thanked them for their help.

Results and discussion of awareness check study

Inspection of the responses revealed that only 1 of the 19 participants showed any awareness of a relationship between the stimulus words and the elderly stereotype. However, even this participant could not predict in what form or direction their behavior might have been influenced had such an influence occurred.

Thus, it appears safe to conclude that the effect of the elderly priming manipulation on walking speed occurred nonconsciously.

Next time

Priming effect: Replication study