Hype

2024-10-23 Wed

Overview

Announcements

- Discuss draft Friday, October 25

- Final version due Wednesday, October 30

Last time

- When Nuijten, Hartgerink, Assen, Epskamp, & Wicherts (2015) examined 250,000+ statistics in psychology papers published from 1985-2013, what did they find?

- How does the GRIM tool discussed by Brown & Heathers (2017) catch errors in reporting Likert-scale-type values?

- Szucs & Ioannidis (2017) found that “Median power to detect small, medium, and large effects was 0.12, 0.44, and 0.73…” Can you restate this in less formal or technical terms?

Today

Hype

- Discuss

- Carney, Cuddy, & Yap (2010), file on Canvas

- (Optional) Ranehill et al. (2015), file on Canvas

https://www.psu.edu/news

- Promoting research important to researchers and institutions

Chapter 6 from Ritchie (2020)

- Problems with scientific press releases

- Not written by scientists

- give unwarranted advice

- cross-species leaps or generalizations

- equating correlation with causation

- “Churnalism”

- Journalists do not do their own investigations but repeat press releases

- Popular books (by scientists, too) can gloss over complexities, nuances

- Positive rhetoric/spin

- Counter-example from OPERA study of faster-than-light particle

Power-posing

Questions

- What claims did Cuddy (2012) make about the effects of power posing on feelings, hormones, and behaviors?

- What claims are well-supported by the empirical evidence in Carney et al. (2010) and Ranehill et al. (2015)?

- What claims are less well-supported?

- Is the Cuddy (2012) talk an example of research hype? Why or why not?

Cuddy (2012)

Amy Cuddy’s TED talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_may_shape_who_you_are

Citation data

Talk viewed ~69.5 million times according to TED web page on 2023-10-16.

Carney, D. R., Cuddy, A. J. C. & Yap, A. J. (2010). Power posing: Brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1363–1368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610383437

Humans and other animals express power through open, expansive postures, and they express powerlessness through contractive postures. But can these postures actually cause power?

Carney et al. (2010)

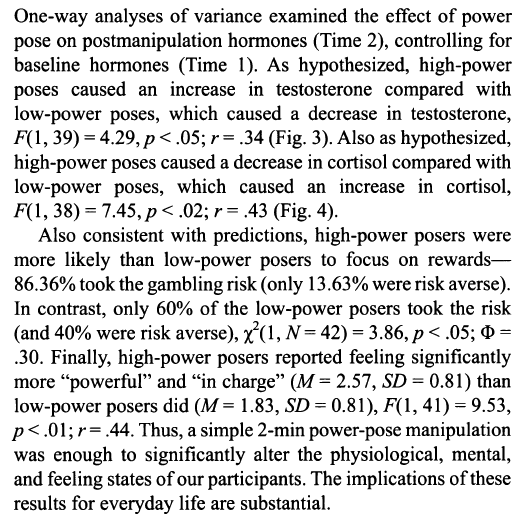

The results of this study confirmed our prediction that posing in high-power nonverbal displays (as opposed to low-power nonverbal displays) would cause neuroendocrine behavioral changes for both male and female participants: High-power posers experienced elevations in testosterone, decreases in cortisol, and increased feelings of power and tolerance for risk; low-power posers exhibited the opposite pattern.

Carney et al. (2010)

In short, posing in displays of power caused advantaged and adaptive psychological, physiological, and behavioral changes, and findings suggest that embodiment extends beyond mere thinking and feeling, to physiology and subsequent behavioral choices. That a person can, by assuming two simple 1-min poses, embody power and instantly become more powerful has real-actionable implications.

Carney et al. (2010)

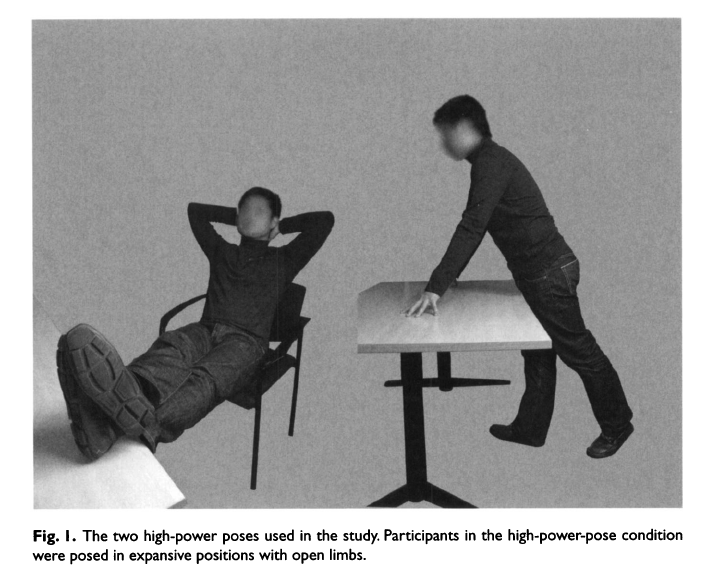

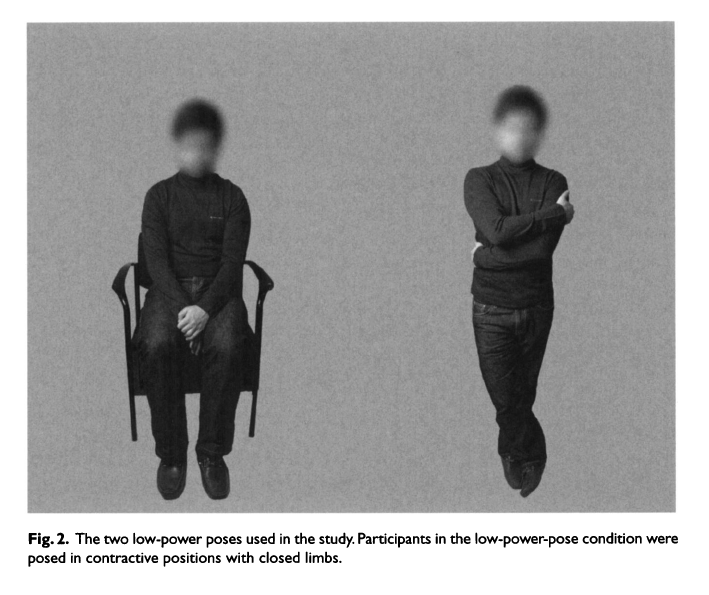

Methods

- \(n=42\) participants (26 female)

- age or other characteristics not reported

- Assigned into two groups (high power vs. low power)

- Experimenter posed bodies

- Two different poses held for 1 min

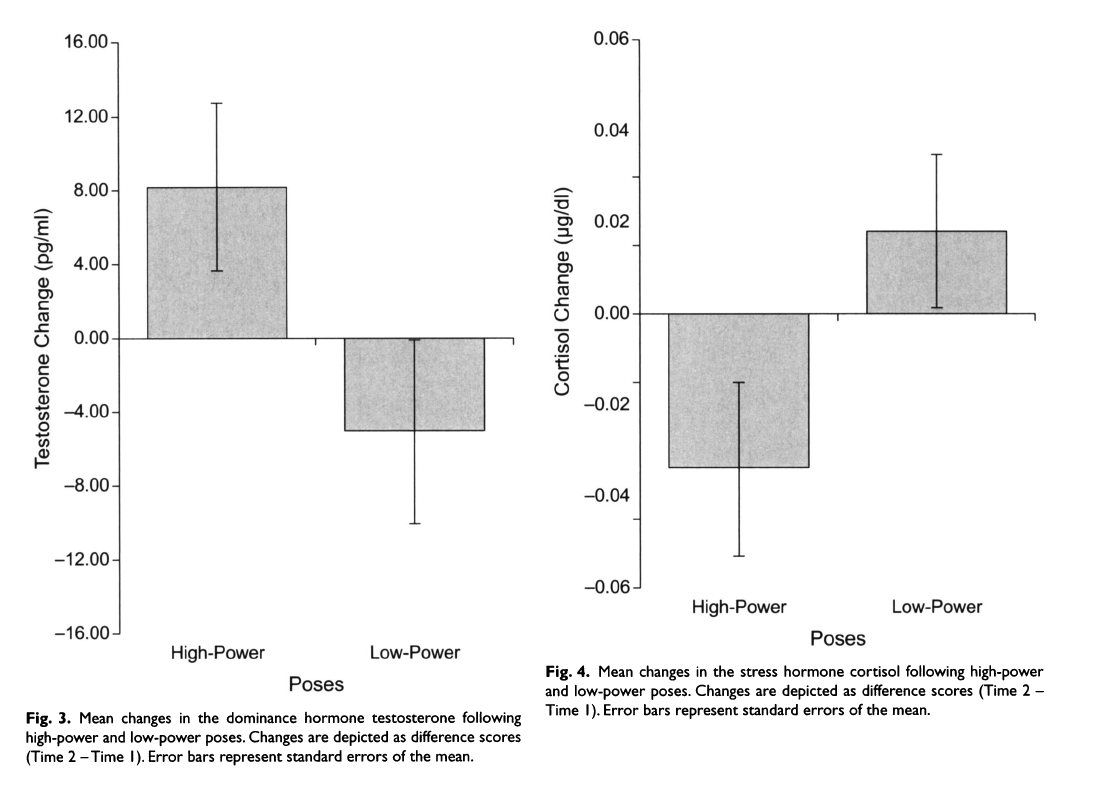

Figure 1 from Carney et al. (2010)

Low power poses. Figure 2 from Carney et al. (2010)

- Other tasks/measures

- Gambling task (risk-taking, powerful feelings)

- Self-reported feelings of power

- Saliva samples (pretest and ~ 17 min after pose)

- Tested for cortisol, testosterone

Results

Carney et al. (2010)

Figure 3 from Carney et al. (2010)

Citation data

Paper cited ~1,700 times:

according to Google Scholar as of 2024-10-23.

Reproducibility notes

- Article was behind a paywall.

- PDF was available via authenticated access to PSU Libraries.

- No data are shared; no code used to make the figures or conduct the analyses were shared.

Presentation comments

- Gilmore prefers graphs that show individual participant data points (see supplemental document).

A replication attempt

Ranehill, E., Dreber, A., Johannesson, M., Leiberg, S., Sul, S. & Weber, R. A. (2015). Assessing the robustness of power posing: no effect on hormones and risk tolerance in a large sample of men and women [Review of Assessing the robustness of power posing: no effect on hormones and risk tolerance in a large sample of men and women]. Psychological Science, 26(5), 653–656. journals.sagepub.com. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614553946

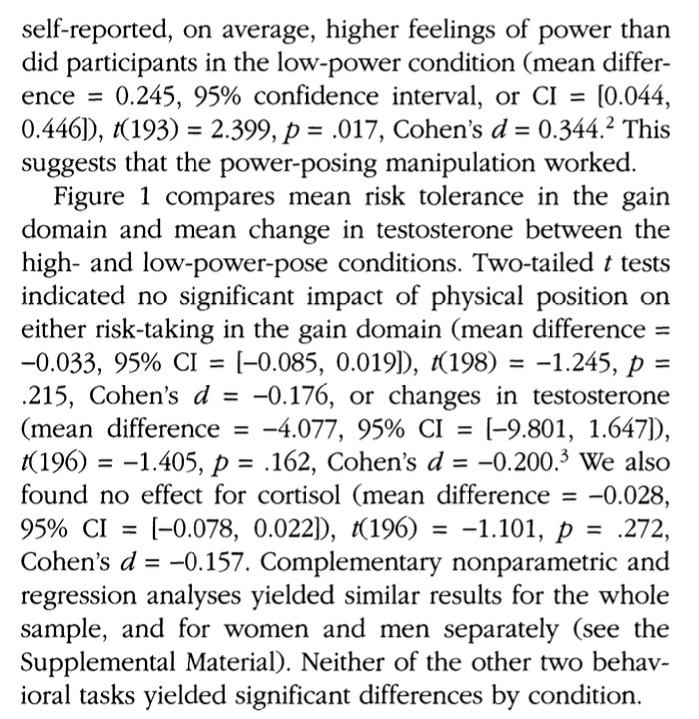

We conducted a conceptual replication study task with a similar methodology as that employed by Carney et al. but using a substantially larger sample (N=200) and a design in which the experimenter was blind to condition.

Ranehill et al. (2015)

Our statistical power to detect an effect of the magnitude reported by Carney et al. was more than 95% (see the Supplemental Material available online). In addition to the three outcome measures that Carney et al. used, we also studied two more behavioral tasks (risk taking in the loss domain and willingness to compete).

Ranehill et al. (2015)

Consistent with the findings of Carney et al., our results showed a significant effect of power posing on self-reported feelings of power. However, we found no significant effect of power posing on hormonal levels in any of the three behavioral tasks.

Ranehill et al. (2015)

Methods

- Sampled \(n=100\) after power analysis; then sampled another 100.

- 3 min pose durations

- Participants modeled poses following computer instructions.

- No deception.

Results

Ranehill et al. (2015)

Figure 1 from Ranehill et al. (2015)

Citation data

Paper cited ~360 times:

according to Google Scholar on 2024-10-23.

Reproducibility notes

- Article was behind a paywall.

- The PDF was available via authenticated access to PSU Libraries.

- The PDF did not easily permit cutting and pasting of text, so it was hard to excerpt those for this document.

- The HTML version of the article was unavailable, so I had to make screenshots of figures.

- There is an OSF site with data and materials.

- The OSF site includes very helpful details about the experiments.

- The data and code were shared, but I don’t have access to the statistical program used (Stata) to rerun the analysis. The data had a

.dtafile extension. This appears to be a plain text, ‘tidy’ data file format that could be used by another program.

Note

The New York Times published an article by Dominus (2017) on the controversy surrounding Dr. Cuddy’s work called “When the Revolution Came for Amy Cuddy.”

I considered reading this and discussing it, but I was more interested in the substantive claims made in the papers and in the talk.

Reading the Times’ story and discussing the controversy would make a great final project topic, however.

Next time

- Discuss draft