A replication crisis

Roadmap

- Announcements

- Last time…

- Scientific norms and counter-norms

- Readings

- Survey results

- Today’s topics

- A replication crisis…or not

- Read

- (Ritchie, 2020), Chapter 2. PDF on Canvas.

- Begley & Ellis (2012)

- (Optional) (Oreskes, 2019), Chapter 7, pp. 228-244

Replication crisis…or not

What proportion of findings in the published scientific literature (in the fields you care about) are actually true?

- 100%

- 90%

- 70%

- 50%

- 30%

How widespread is the problem?

](http://www.nature.com/polopoly_fs/7.36716.1469695923!/image/reproducibility-graphic-online1.jpeg_gen/derivatives/landscape_630/reproducibility-graphic-online1.jpeg)

Figure 30: M. Baker (2016)

](http://www.nature.com/polopoly_fs/7.36718.1464174471!/image/reproducibility-graphic-online3.jpg_gen/derivatives/landscape_630/reproducibility-graphic-online3.jpg)

Figure 31: M. Baker (2016)

](http://www.nature.com/polopoly_fs/7.36719.1464174488!/image/reproducibility-graphic-online4.jpg_gen/derivatives/landscape_630/reproducibility-graphic-online4.jpg)

Figure 32: M. Baker (2016)

These questions could form the basis of a final project where a student or students re-run the survey with a different sample.

What do the terms mean?

Replication refers to testing the reliability of a prior finding with different data. Robustness refers to testing the reliability of a prior finding using the same data and a different analysis strategy. Reproducibility refers to testing the reliability of a prior finding using the same data and the same analysis strategy (Natl. Acad. Sci. Eng. Med. 2019). Each of the three notions plays an important role in assessing credibility.

In principle, all reported evidence should be reproducible. If someone applies the same analysis to the same data, the same result should occur. Reproducibility tests can fail for two reasons. A process reproducibility failure occurs when the original analysis cannot be repeated because of the unavailability of data, code, information needed to recreate the code, or necessary software or tools. An outcome reproducibility failure occurs when the reanalysis obtains a different result than the one reported originally. This can occur because of an error in either the original or the reproduction study.

Different types of reproducibility? Goodman, Fanelli, & Ioannidis (2016)

Methods reproducibility

- Enough details about materials & methods recorded (& reported)

- Same results with same materials & methods

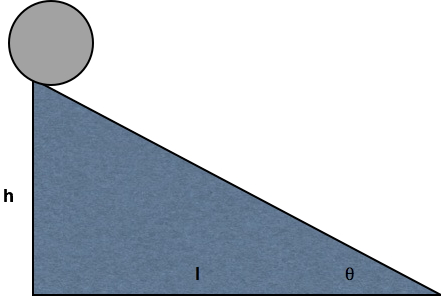

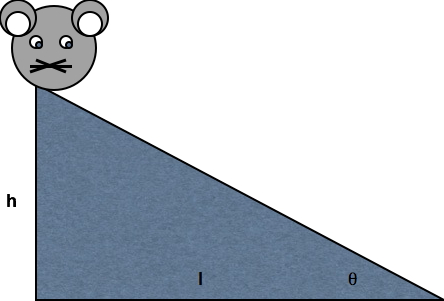

Figure 33: If you got hit by a bus, could your colleagues replicate and build on your work? What’s your project’s ‘bus number’?

Reproducibility in psychological science

Artner et al. (2021)

We investigated the reproducibility of the major statistical conclusions drawn in 46 articles published in 2012 in three APA journals. After having identified 232 key statistical claims, we tried to reproduce, for each claim, the test statistic, its degrees of freedom, and the corresponding p value, starting from the raw data that were provided by the authors and closely following the Method section in the article. Out of the 232 claims, we were able to successfully reproduce 163 (70%), 18 of which only by deviating from the article’s analytical description. Thirteen (7%) of the 185 claims deemed significant by the authors are no longer so. The reproduction successes were often the result of cumbersome and time-consuming trial-and-error work, suggesting that APA style reporting in conjunction with raw data makes numerical verification at least hard, if not impossible.

Collaboration (2015)

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716–aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

- Read and discuss on Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Camerer et al. (2018)

Camerer, C. F., Dreber, A., Holzmeister, F., Ho, T.-H., Huber, J., Johannesson, M., Kirchler, M., Nave, G., Nosek, B. A., Pfeiffer, T., Altmejd, A., Buttrick, N., Chan, T., Chen, Y., Forsell, E., Gampa, A., Heikensten, E., Hummer, L., Imai, T., … Wu, H. (2018). Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nature Human Behaviour, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0399-z

- Read and discuss on Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Whitt, Miranda, & Tullett (2022)

Whitt, C. M., Miranda, J. F. & Tullett, A. M. (2022). History of Replication Failures in Psychology. In W. O’Donohue, A. Masuda & S. Lilienfeld (Eds.), Avoiding Questionable Research Practices in Applied Psychology (pp. 73–97). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04968-2_4

Reproducibility in pre-clinical cancer biology

- Reading: Begley & Ellis (2012)

- Discuss replication in cancer biology on Thursday, February 2, 2023.

Background

The scientific community assumes that the claims in a preclinical study can be taken at face value — that although there might be some errors in detail, the main message of the paper can be relied on and the data will, for the most part, stand the test of time. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Over the past decade, before pursuing a particular line of research, scientists (including C.G.B.) in the haematology and oncology department at the biotechnology firm Amgen in Thousand Oaks, California, tried to confirm published findings related to that work. Fifty-three papers were deemed ‘landmark’ studies (see ‘Reproducibility of research findings’). It was acknowledged from the outset that some of the data might not hold up, because papers were deliberately selected that described something completely new, such as fresh approaches to targeting cancers or alternative clinical uses for existing therapeutics. Nevertheless, scientific findings were confirmed in only 6 (11%) cases. Even knowing the limitations of preclinical research, this was a shocking result.

| Journal Impact Factor | \(n\) articles | Mean number of citations for non-reproduced articles | Mean number of citations of reproduced articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| >20 | 21 | 248 [3, 800] | 231 [82-519] |

| 5-19 | 32 | 168 [6, 1,909] | 13 [3, 24] |

Table 1 from Begley & Ellis (2012)

Findings

- Findings of 6/53 published papers (11%) could be reproduced

- Original authors often could not reproduce their own work

- Earlier paper Prinz et al. (2011) had also found low rate of reproducibility. Paper titled “Believe it or not: How much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets?”

- Figure 1 from Prinz et al. (2011)

We received input from 23 scientists (heads of laboratories) and collected data from 67 projects, most of them (47) from the field of oncology. This analysis revealed that only in ∼20–25% of the projects were the relevant published data completely in line with our in-house findings

- Published papers (that can’t be reproduced) are cited hundreds or thousands of times

- Cost of irreproducible research estimated in billions of dollars Freedman et al. (2015).

An analysis of past studies indicates that the cumulative (total) prevalence of irreproducible preclinical research exceeds 50%, resulting in approximately US$28,000,000,000 (US$28B)/year spent on preclinical research that is not reproducible—in the United States alone.

- Figure 2 from Freedman et al. (2015)

- Information about U.S. Research & Development (R&D) expenditures from the Congressional Research Service.

- Note that business accounts for 2-3x+ the Government’s share of R&D expenditures.

Questions to ponder

- Why do Begley & Ellis focus on a journal’s impact factor?

- Why do Begley & Ellis focus on citations to reproduced vs. non-reproduced articles?

- Why should non-scientists care?

- Why should scientists in other fields (not cancer biology) care?

Learn more

Talk by Begley CrossFit (2019)

“What I’m alleging is that the reviewers, the editors of the so-called top-tier journals, grant review committees, promotion committees, and the scientific community repeatedly tolerate poor-quality science.”

– C. Glenn Begley

Watching the talk by Begley is not required. But you might get inspired and decide to focus your final project around the topic.

Brian A. Nosek et al. (2022)

Nosek, B. A., Hardwicke, T. E., Moshontz, H., Allard, A., Corker, K. S., Dreber, A., Fidler, F., Hilgard, J., Kline Struhl, M., Nuijten, M. B., Rohrer, J. M., Romero, F., Scheel, A. M., Scherer, L. D., Schönbrodt, F. D. & Vazire, S. (2022). Replicability, robustness, and reproducibility in psychological science. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(2022), 719–748. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-114157

Replication—an important, uncommon, and misunderstood practice—is gaining appreciation in psychology. Achieving replicability is important for making research progress. If findings are not replicable, then prediction and theory development are stifled. If findings are replicable, then interrogation of their meaning and validity can advance knowledge. Assessing replicability can be productive for generating and testing hypotheses by actively confronting current understandings to identify weaknesses and spur innovation. For psychology, the 2010s might be characterized as a decade of active confrontation. Systematic and multi-site replication projects assessed current understandings and observed surprising failures to replicate many published findings. Replication efforts highlighted sociocultural challenges such as disincentives to conduct replications and a tendency to frame replication as a personal attack rather than a healthy scientific practice, and they raised awareness that replication contributes to self-correction. Nevertheless, innovation in doing and understanding replication and its cousins, reproducibility and robustness, has positioned psychology to improve research practices and accelerate progress.

Peng & Hicks (2021)

Peng, R. D. & Hicks, S. C. (2021). Reproducible research: A retrospective. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-012420-105110

Advances in computing technology have spurred two extraordinary phenomena in science: large-scale and high-throughput data collection coupled with the creation and implementation of complex statistical algorithms for data analysis. These two phenomena have brought about tremendous advances in scientific discovery but have raised two serious concerns. The complexity of modern data analyses raises questions about the reproducibility of the analyses, meaning the ability of independent analysts to recreate the results claimed by the original authors using the original data and analysis techniques. Reproducibility is typically thwarted by a lack of availability of the original data and computer code. A more general concern is the replicability of scientific findings, which concerns the frequency with which scientific claims are confirmed by completely independent investigations. Although reproducibility and replicability are related, they focus on different aspects of scientific progress. In this review, we discuss the origins of reproducible research, characterize the current status of reproducibility in public health research, and connect reproducibility to current concerns about the replicability of scientific findings. Finally, we describe a path forward for improving both the reproducibility and replicability of public health research in the future.

Reading and writing a commentary on either of these articles might be a good final project.