Adherence to norms and counter-norms

Roadmap

- Last time

- Scientific norms and counter-norms

- Readings

- Survey results

- Assignment

How to read a paper

- What type of paper is it? Empirical, theoretical, review, opinion, other?

- Read the abstract carefully for answers to the following questions:

- Who is the target audience?

- Why did the author(s) do this work? What question were they trying to answer or what view were they trying to argue for?

- What is the take-home message or main finding(s)?

- For empirical papers, Who were the participants? What were their characteristics? What was measured? When or how often were the measurements taken?

- Read the Methods section

- Look at the figures in the Results section

- Do the figures “tell the story” of the paper?

- Imagine how you would complete the following synthesis: “This paper asks X by measuring Y in Z. It found Q, which suggests R. The paper is flawed because of S.”

- Read the Introduction and/or the Discussion if you need or want to know more.

Other tips

- Highlight/flag unfamiliar terms or acronyms, but don’t stop reading to look them up until later.

- Keep a reference manager program; grab papers and sift through them later.

Discuss Kardash & Edwards (2012)

Kardash, C. M. & Edwards, O. V. (2012). Thinking and behaving like scientists: Perceptions of undergraduate science interns and their faculty mentors. Instructional Science, 40(6), 875–899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9195-0

Figure 18: CarolAnne M. Kardash: Source https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/las-vegas-nv/carolanne-kardash-10908219

Abstract

We examined undergraduate research experiences (UREs) participants’ and their faculty mentors’ beliefs about the professional practices and dispositions of research scientists. In Study 1, 63 science interns and their mentors rated Merton’s (J Legal Political Sociol, 1:115–126, 1942) norms and Mitroff’s (Am Sociol Rev, 39(August):579–595, 1974) counter-norms of scientific practice. Specifically, we investigated what practices they believed research scientists should subscribe to (or not), and what practices they believed actually characterized research scientists’ behavior in the real world. Regarding idealized practice, mentors rated the norms significantly higher than did interns; mentors and interns generally did not differ in subscription to the counter-norms. Regarding actual practice, mentors believed scientists’ behaviors reflected counter-norms more than norms. Mentors further noted discrepancies between practices that should represent and actually did represent scientists’ work. In Study 2, interns and mentors listed characteristics associated with “thinking” and “behaving” like scientists. Personal and professional dispositions were mentioned more than intellectual and research skills. Although there was considerable consensus between faculty and intern perceptions, findings also revealed discrepancies that could be addressed in UREs, thereby aiding undergraduates’ socialization into the culture of scientific practice. Suggestions are provided for broadening interns’ conceptions of both scientists and science.

…uncovering science majors’ conceptions of one aspect of academic life in the sciences—namely, what it means to think and behave like a research scientist. Specifically, we compared science undergraduates’ and faculty mentors’ perceptions of the practices and personal characteristics of research scientists.

As students find themselves immersed in the day to day practices of researchers, what values, practices, and dispositions capture their attention, become most salient to them and provide the foundation for their beliefs about what constitutes the professional identity of research scientists? As important, to what extent are students’ perceptions of these values, practices, and dispositions congruent with the perceptions of the faculty mentors?

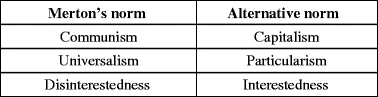

Constantinides (2001) provides the following descriptions of the norms (p. 63):

Universalism requires that knowledge claims be subjected to pre-established, impersonal criteria.

Communality dictates that research belongs to the community of scientists rather than the individual researcher.

Disinterestedness prescribes disinterested scientific activity, which is enforced by the accountability of scientists to their peers.

Organized skepticism requires that claims be critically scrutinized in terms of empirical and logical criteria.

Study 1

](https://media.springernature.com/full/springer-static/image/art%3A10.1007%2Fs11251-011-9195-0/MediaObjects/11251_2011_9195_Fig1_HTML.gif?as=webp)

Figure 19: Figure 1 from Kardash & Edwards (2012)

How do our results compare?

A student could extend this analysis or do additional analyses as a final project.

Discuss Macfarlane & Cheng (2008)

Macfarlane, B. & Cheng, M. (2008). Communism, universalism and disinterestedness: Re-examining contemporary support among academics for Merton’s scientific norms. Journal of Academic Ethics, 6(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y

Figure 20: Bruce Macfarlane: https://hk.linkedin.com/in/bruce-macfarlane-244582a1

Figure 21: Ming Cheng: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=4o9OsswAAAAJ&hl=en

Abstract

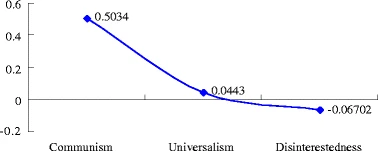

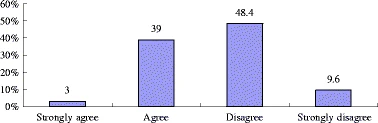

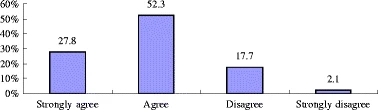

This paper re-examines the relevance of three academic norms to contemporary academic life – communism, universalism and disinterestedness – based on the work of Robert Merton. The results of a web-based survey elicited responses to a series of value statements and were analysed using the weighted average method and through cross-tabulation. Results indicate strong support for communism as an academic norm defined in relation to sharing research results and teaching materials as opposed to protecting intellectual copyright and withholding access. There is more limited support for universalism based on the belief that academic knowledge should transcend national, political, or religious boundaries. Disinterestedness, defined in terms of personal detachment from truth claims, is the least popular contemporary academic norm. Here, the impact of a performative culture is linked to the need for a large number of academics to align their research interests with funding opportunities. The paper concludes by considering the claims of an alternate set of contemporary academic norms including capitalism, particularism and interestedness.

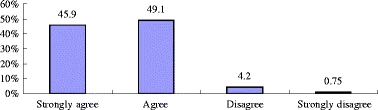

Figure 22: Fig 1: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/1

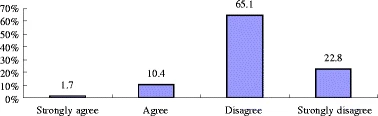

Figure 23: Fig 2: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/2

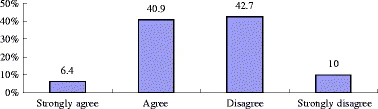

Figure 24: Fig 3: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/3

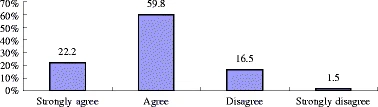

Figure 25: Fig 4: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/4

Figure 26: Fig 5: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/5

Figure 27: Fig 6: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/6

Figure 28: Fig 7: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/7

Figure 29: Fig 8: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10805-008-9055-y/figures/8

Conclusion

The results of the survey do not necessarily represent a ‘shift’ in values as Merton’s norms were not based on empirical data. While this research sample was broadly representative of academic staff by gender, this does not necessarily imply that it is representative of the academic profession in all respects. However, contemporary performative pressures on academic life may be having an impact in shaping, or perhaps re-shaping, some Mertonian norms. This is particularly apparent in respect to the norm of disinterestedness where large numbers of academics pragmatically align their research interests with funding opportunities. This finding may be related to a more competitive market-based university environment apparent in the UK and elsewhere internationally where it has been argued that the canons of scientific inquiry have been compromised by commercial pressures (Bok 2003). Despite these pressures, the norm of communism, in particular, still attracts strong popular espoused support which crosses disciplinary fields. The balance of evidence from this survey, though, suggests that market-based and commercial pressures might be beginning to subvert the Mertonian ideal. However, respondents’ support of universalism and disinterestedness varies with their subjects. In general, respondents from applied sciences showed stronger support for these two norms than respondents from the other subject fields.

This paper would be slightly harder to reproduce as a final project, but something similar is possible.

Looking ahead…

- Assignment

- Exercise 01: Norms and counter-norms write-up

- Due next Thursday, January 26.

- Replication crisis (or not)

- Read

- (Ritchie, 2020), Chapter 2.

- Begley & Ellis (2012)

- (Optional) (Oreskes, 2019), Chapter 7, pp. 228-244.

- Read