Evolution

PSY 511.003

Evolution of Nervous Systems

Public acceptance of evolution

- In U.S., majority now “accept”

- Increase over last decade

Types of evidence

- Fossil

- Fossil dating

- Geological

- Where fossils are found relative to one another

- How long it takes to form layers

- Genetic

- Rates of mutation

- Anatomical

- Homologous structures across species

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense except in the Light of Evolution

“Seen in the light of evolution, biology is, perhaps, intellectually the most satisfying and inspiring science. Without that light, it becomes a pile of sundry facts some of them interesting or curious, but making no meaningful picture as a whole.”

Why Gilmore thinks the theory so controversial (in the U.S.)

- Contradicts verbatim/non-metaphorical reading of some religious texts

- Makes humans seem less special

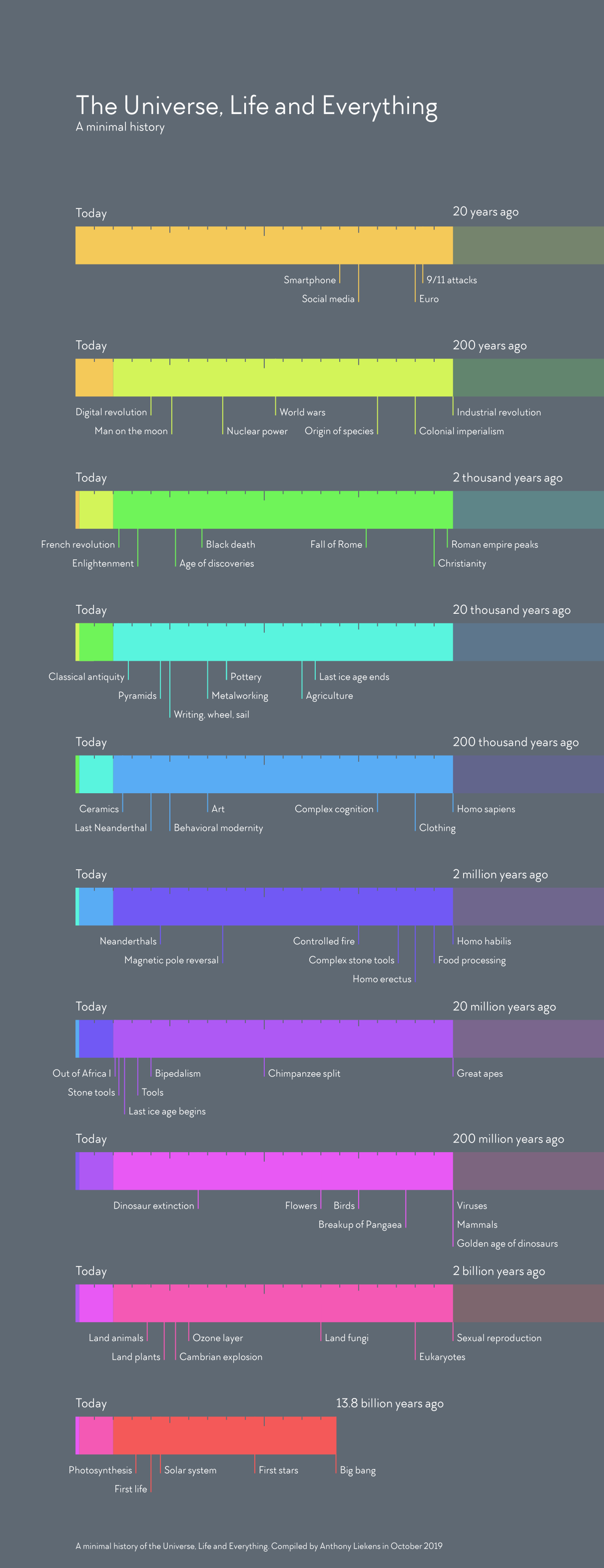

- Time scales involved beyond human experience

- Scientific method vs. other ways of knowing

- Found in nature ≠ good for human society

- Few negative consequences of ‘disbelief’

- U.S. culture individualistic, skeptical, anti-elitist, anti-intellectual

- Lower levels of religious belief among U.S. scientists

- Politics

- A minority of citizens support teaching evolution-only

- Majority of classroom teachers aren’t strong advocates

A structural equation model indicates that increasing enrollment in baccalaureate-level programs, exposure to college-level science courses, a declining level of religious fundamentalism, and a rising level of civic scientific literacy are responsible for the increased level of public acceptance.

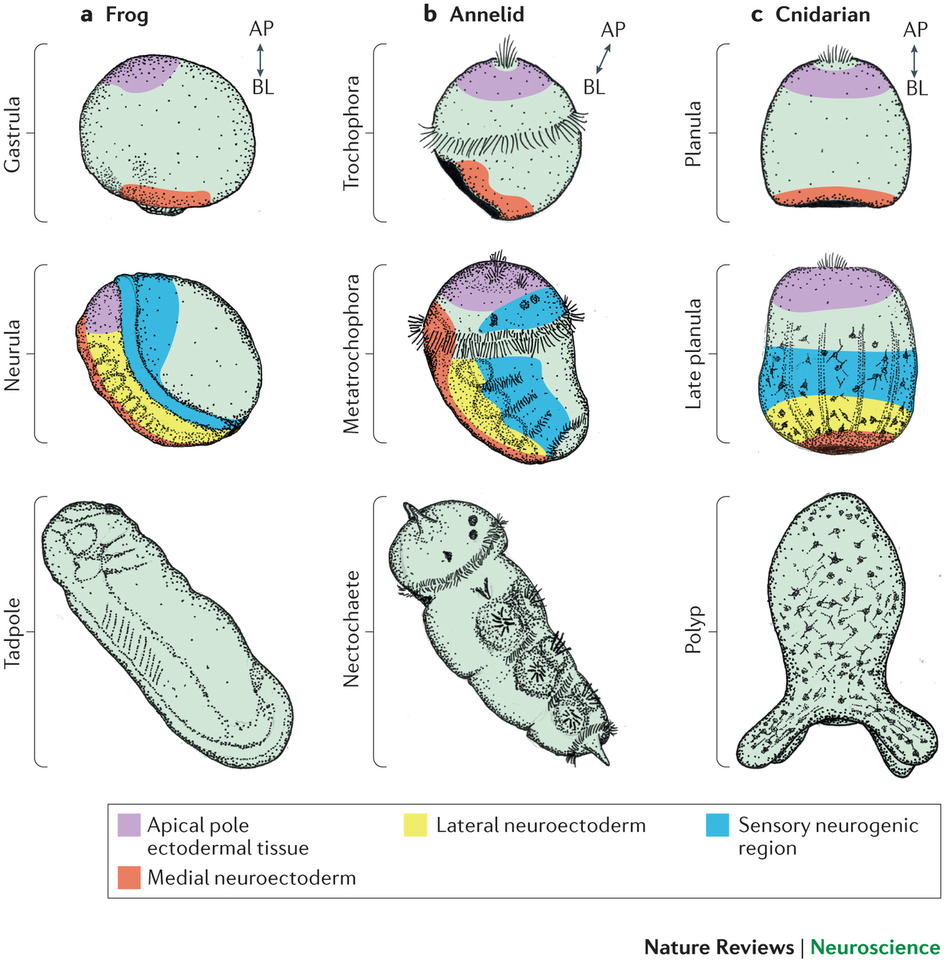

Evolution and development

Ontogenesis and phylogenesis

- Ontogenesis

- Development within lifetimes, history of individuals

- Phylogenesis

- Change across lifestimes, history of species

Ontogeny does not recapitulate phylogeny (Haeckel), but…

Complex multicellular life emerged “recently”

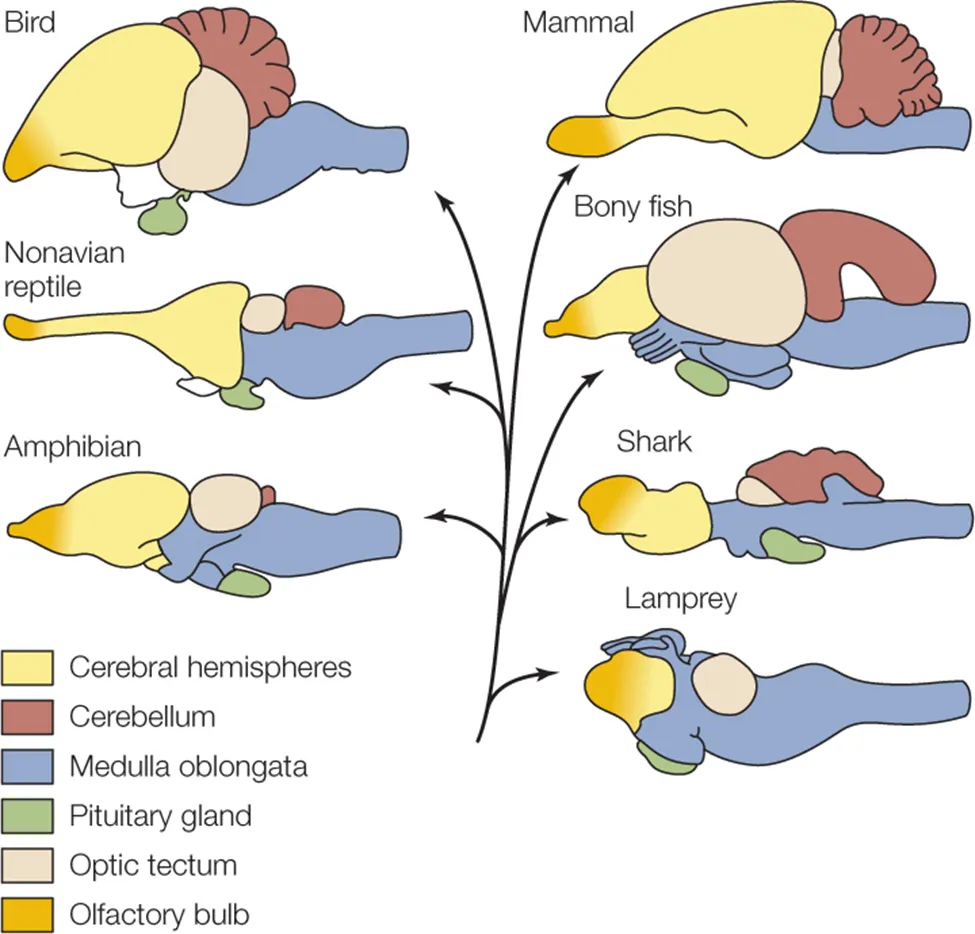

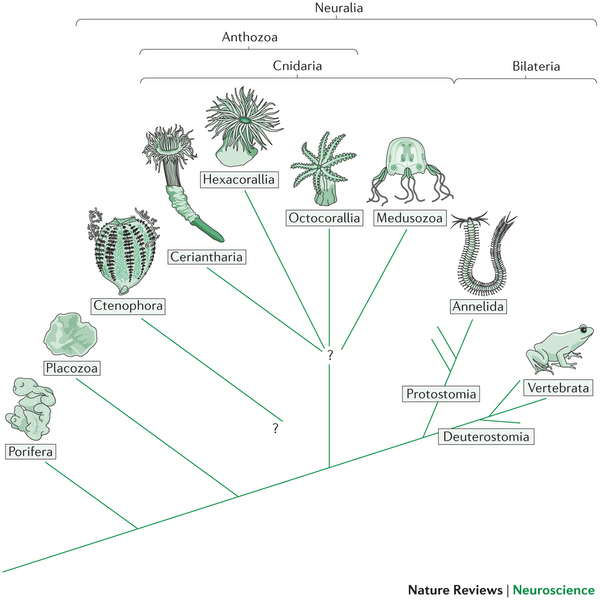

Nervous system architectures

How nervous systems differ

- Body symmetry

- radial

- bilateral

An animal with a nerve “net”

- Segmentation

- Cephalization (concentration of sensory & neural structures in anterior portion of body)

- Encasement in bone (vertebrates)

- Centralized vs. distributed function

Cephalopods have “intelligent arms”

The essentials of biological computation

- Ingestion

- Defense

- Reproduction

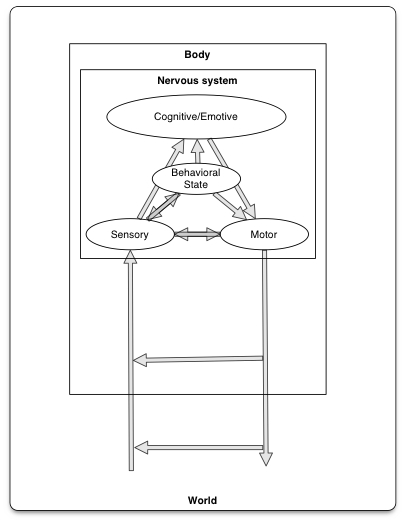

Information processing universals

- Sense/detect via sensors

- Specialize by information source/type

- Specialize by target location

- Interoceptive

- Exteroceptive

- Analyze, evaluate, decide

- Current state

- World

- Organism

- Current goals

- Past state(s)

- Current state

- Act

- Move body

- Approach/avoid

- Manipulate

- Ingest

- Signal

- Change physiological state

- Move body

From nerve net to nerve ring, nerve cord, and brain

- Neurons and nervous systems 520-570 M years old

- Diverse nervous systems show developmental similarities at molecular level

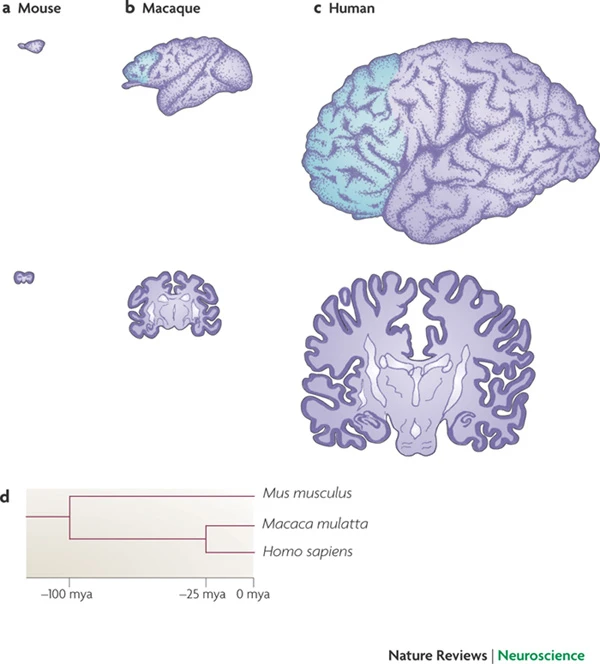

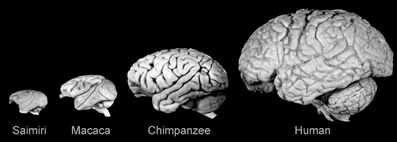

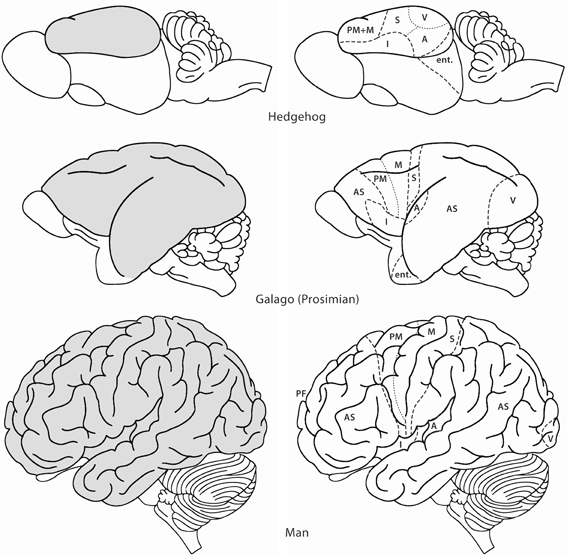

Vertebrate CNS organization

- Differences in size of the cerebral cortex

| Structural measure | Non-human comparison | Human |

|---|---|---|

| Cortical gray matter %/tot brain vol | insectivores 25% | 50% |

| Cortical gray + white | mice 40% | 80% |

| Cerebellar mass | primates, mammals 10-15% | 10-15% |

- Evidence for greater gray and white matter (relative to total brain volume) in human cerebral cortex

Take homes

- Brain sizes scale with body size

- Brain sizes (more or less) scale with animal class (more or less)

Old story

- Within mammals, human brains bigger than expected

- Higher encephalization quotient – deviation from species-typical norm

- Humans have larger cerebral cortical gray + white matter than comparable mammals

vs. New story

- Does brain size/mass matter (that much)?

- “Size matters” (brain mass) presumes similarity among brains at micro-level

- Big (large mass) brains arise in multiple mammalian lineages

- # of cortical neurons more important difference than brain mass

- The primate advantage -> more cortical neurons, but not larger neurons & not more neurons in cerebellum

- Human brain just scaled up (non-ape) primate brain

# of cortical (or in birds, pallidum) neurons predicts “cognition”?

The Human Advantage (Herculano-Houzel, 2016)

- Brain

- More neurons in cerebral cortex than other mammals

- Behavior

- Less time spent foraging

- Higher quality/more energetically dense food

- Higher food availability

- Cultural factors (agriculture + cooking), see also (Wrangham, 2009)

- Less time spent foraging

A further human advantage