Neuroscience methods

PSY 511.003

Evaluating methods

What are we measuring?

- Structure

- Activity

- Why not function?

What is the question?

- Structure X -> Structure Y

- Structure X -> Function Y

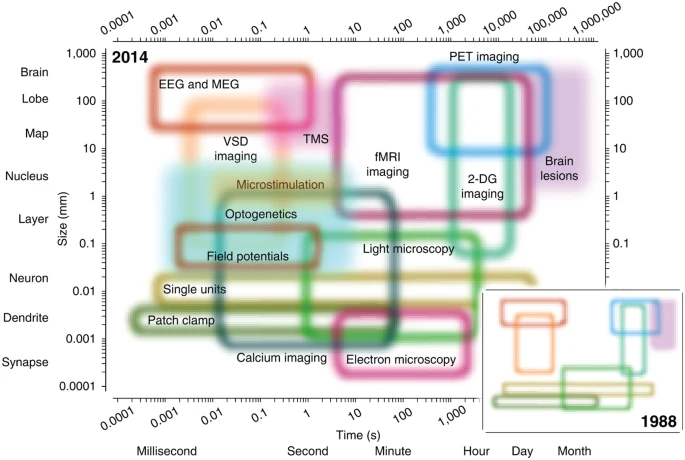

Strengths & Weaknesses

- Cost

- Invasiveness

- Spatial/temporal resolution

Spatial resolution

…and temporal resolution

Types of methods

- Structural

- Anatomy

- Connectivity/connectome

- Functional

- What does it do?

- Physiology/Activity

Structural methods

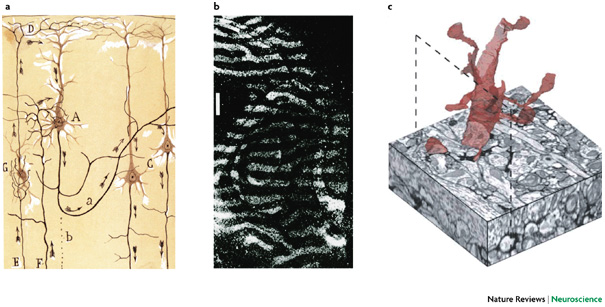

Mapping microstructure

- Cell/axon stains

- Cellular distribution, concentration, microanatomy

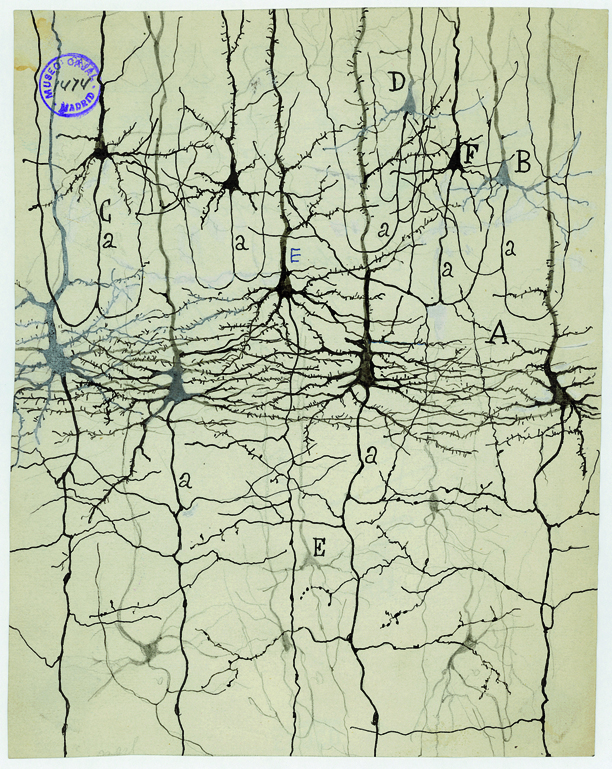

Golgi stain

- whole cells, but small % of total

Camillo Golgi

Nissl stain

- Only cell bodies

- Cell density ~ color intensity

Franz Nissl

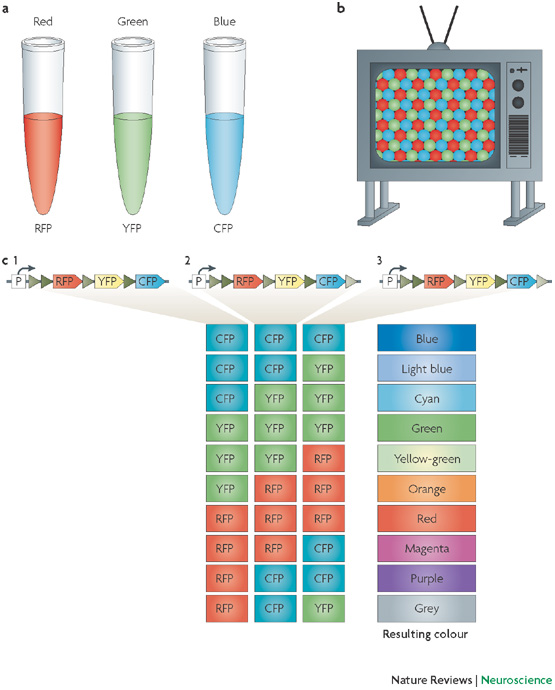

Brainbow

Clarity

CUBIC

- CUBIC (“clear, unobstructed brain/body imaging cocktails and computational analysis”)

- (Susaki et al., 2014)

Evaluating micro/cellular techniques

- Invasive (in humans post-mortem only)

- High spatial resolution, but poor/coarse temporal

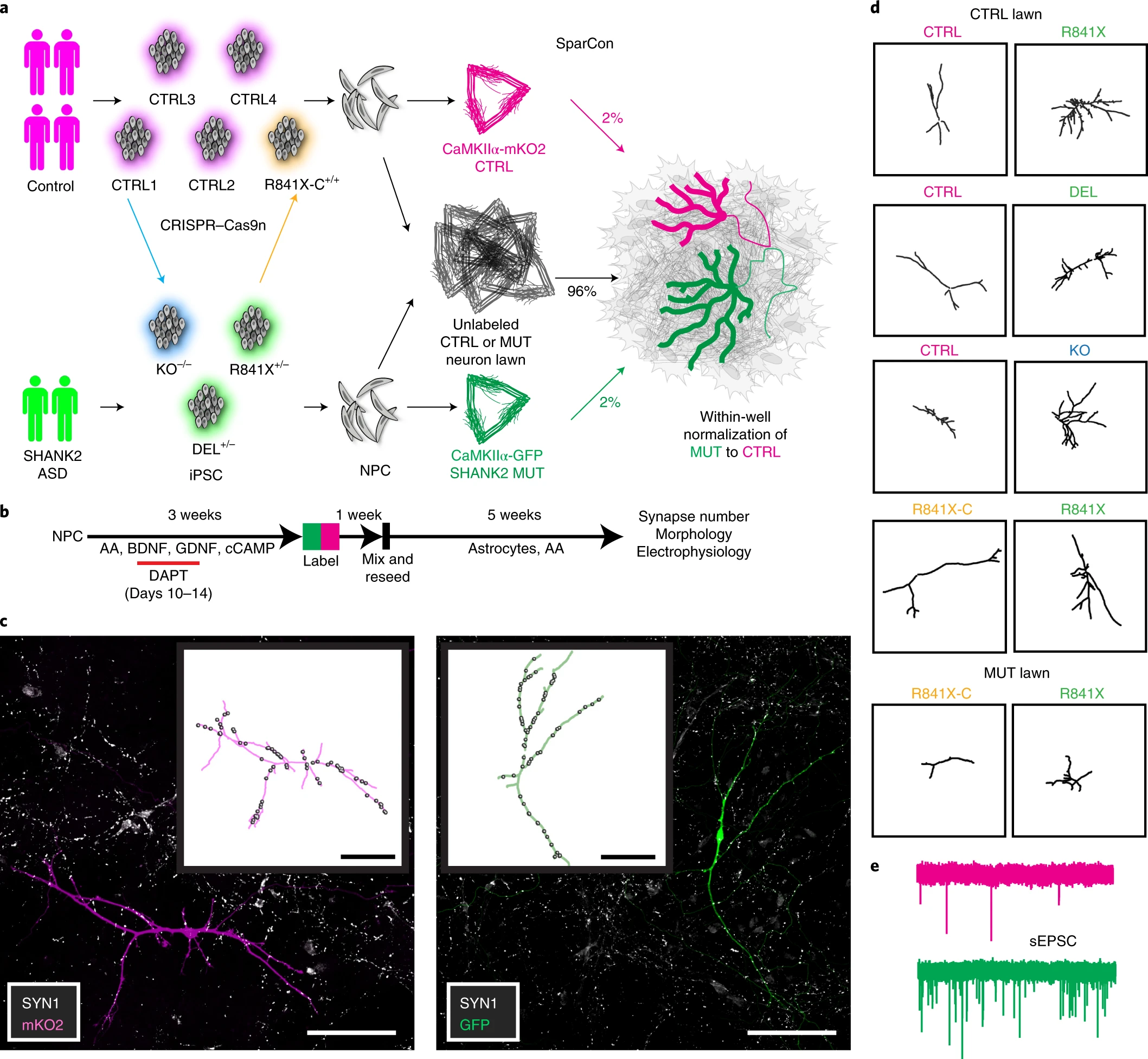

“SHANK2 mutations associated with autism spectrum disorder cause hyperconnectivity of human neurons.” (Zaslavsky et al., 2019)

Mapping macro-structures

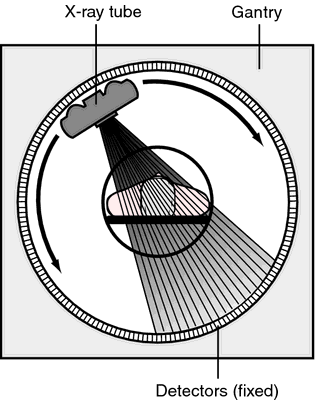

Computed axial tomography (CAT), CT

- X-ray based

Tomography

- Structured sequence of 2D images -> 3D reconstruction

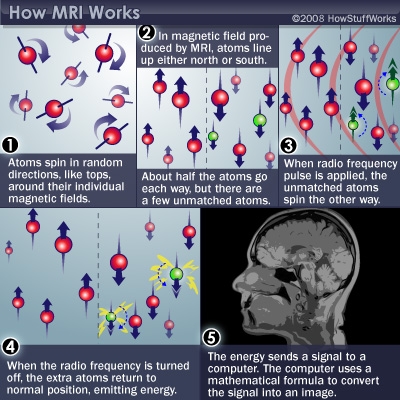

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Magnetic resonance a property of some isotopes and complex molecules

- Hydrogen (\(H\)), common in water & fat, is one

- In magnetic field, \(H\) atoms absorb and release radio frequency (RF) energy

- \(H\) atoms align with strong magnetic field

- Applying RF pulse perturbs alignment

- Rate/timing of realignment varies by tissue

- Realignment gives off radio frequency (RF) signals

- Strength of RF ~ density of \(H\) (or other target)

- \(k\)-space (frequency/phase) -> anatomical space

- Fourier analysis and synthesis important for psychological/neural science, but possibly unfamiliar to many.

- Frequency and phase \(/rightarrow\) amplitude and location

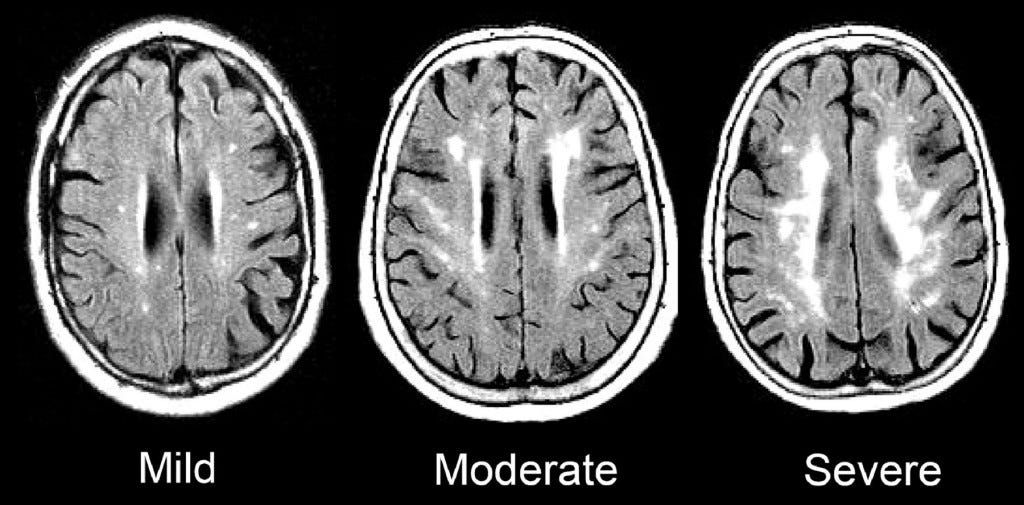

Structural MRI

- Tissue density/type differences

- Gray matter (nerve cells & dendrites) vs. white matter (axon fibers)

MR Spectroscopy (specific metabolites)

- Region sizes/volumes

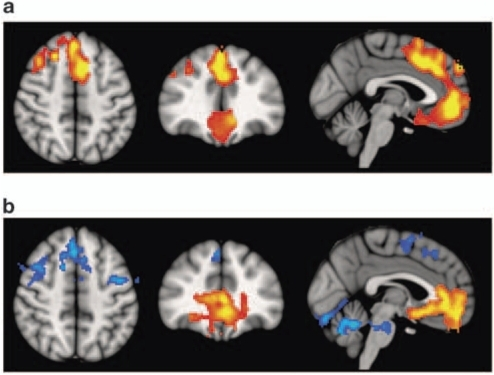

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM)

- MRI technique for measuring brain sizes/volumes

- Volume differences in schizophrenics vs. controls

- Colored portions are statistical maps placed on top of a base structural map.

- Maps (a) provide information about the comparison in brain volumes between patients and controls in those areas, and in (b) functional imaging differences in an n-back task.

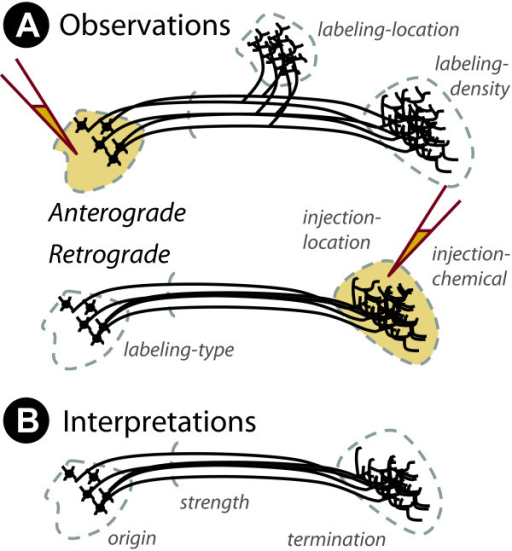

Mapping the wiring diagram (“connectome”)

Microscale

Retrograde (output -> input) vs. anterograde (input -> output) tracers

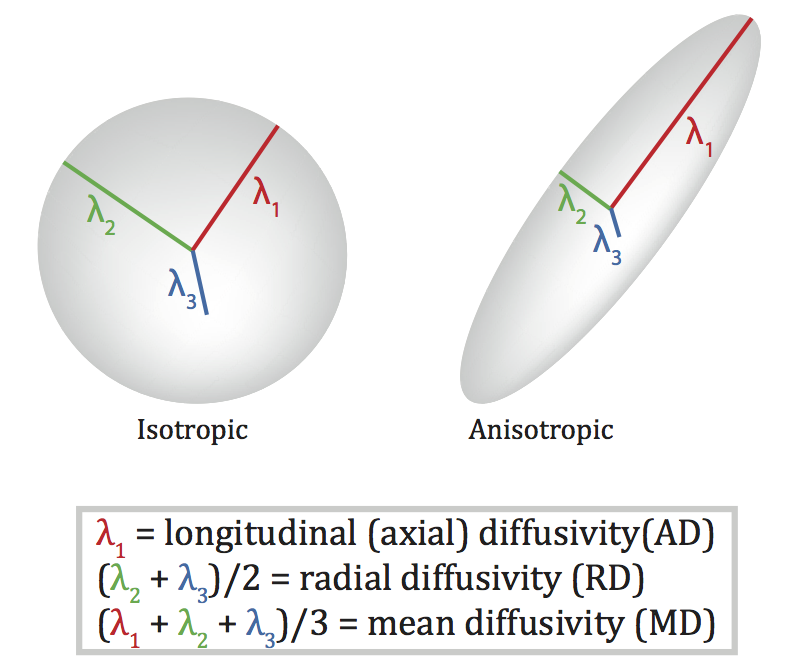

Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI)

- Structural MRI technique

- Diffusion tensor: measurement of spatial pattern of \(H_2O\) diffusion in small volume

- Uniform (“isotropic”) vs. non-uniform (“anisotropic”)

- Strong anisotropy suggests large # of axons with similar orientations (fiber tracts)

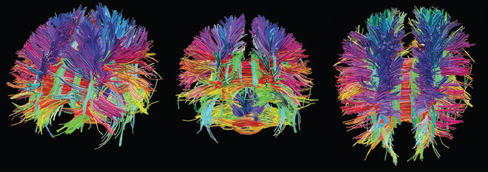

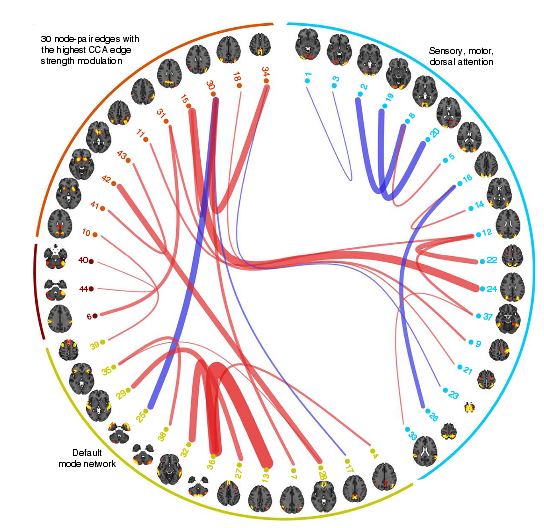

Visualizing the connectome

Functional methods

- Recording from the brain

- Interfering with the brain

- Stimulating the brain

- Simulating the brain

Recording from the brain

Single/multi-unit Recording

- Microelectrodes + amplification

- Small numbers of nerve cells

- What does neuron X respond to?

- How does firing frequency, timing vary with behavior?

- Great temporal (ms), spatial resolution (um)

- Invasive

- Rarely suitable for humans, but…

Electrocorticography (ECoG)

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/GHLBcCv4rqk

- Radioactive tracers (glucose, oxygen)

- Positron decay activates paired detectors

- Tomographic techniques reconstruct 3D geometry

- Experimental condition - control

- Average across individuals

- Temporal (~ s) and spatial (mm-cm) resolution worse than fMRI

- Radioactive exposures + mildly invasive

- Dose < airline crew exposure in 1 yr

Example: Neurotransmitter receptor binding and behavior

Our main finding was that higher DEBQ scores were associated with lower central availability of MORs and CB1Rs in healthy, nonobese humans. MOR and CB1R systems however showed distinct patterns of associations with specific dimensions of self-reported eating: While CB1Rs were associated in general negatively with different DEBQ subscale scores (and most saliently with the Total DEBQ score), MORs were specifically and negatively associated with externally driven eating only. Our results support the view that variation in endogenous opioid and endocannabinoid systems explain interindividual variation in feeding, with distinct effects on eating behavior measured with DEBQ.

Comparing PET and fMRI

The brain’s energy budget can be non-invasively assessed with different imaging modalities such as functional MRI (fMRI) and PET (fPET), which are sensitive to oxygen and glucose demands, respectively. The introduction of hybrid PET/MRI systems further enables the simultaneous acquisition of these parameters…The absence of a correlation and the different activation pattern between fPET and fMRI suggest that glucose metabolism and oxygen demand capture complementary aspects of energy demands.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

- Neural activity -> local \(O_2\) consumption increase

- Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) response

- Oxygenated vs. deoxygenated hemoglobin ≠ magnetic susceptibility

- How do regional blood \(O_2\) levels (& flow & volume) vary with behavior X?

- MRI “signals” relate to the speed (1/T) of “relaxation” of the perturbed nuclei to their state of alignment with the main (\(B_0\)) magnetic field.

- Imaging protocols emphasize different time constants of this relaxation (\(T1\), \(T2\), \(T2^*\)); \(T^{2^*}\) for BOLD imaging

Evaluating fMRI

- Non-invasive, but expensive

- Moderate but improving (mm) spatial, temporal (~sec) resolution

- Spatial limits due to

- field strength (@ 3T \(~3mm^3\) voxel)

- Physiology of hemodynamic response

- Temporal limits due to

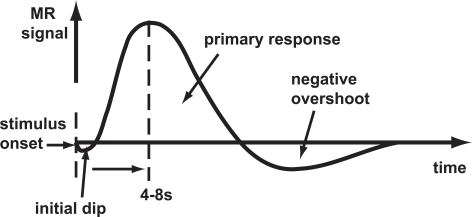

- Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF): ~ 1s delay plus 3-6 s ramp-up

- Speed of image acquisition

- Indirect measure of neural activity

Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF)

Generate “predicted” BOLD response to event; compare to actual

Generate “predicted” BOLD response to event; compare to actual

Higher field strengths (3 Tesla vs. 7 Tesla)

fMRI studies often statistically underpowered

Assuming a realistic range of prior probabilities for null hypotheses, false report probability is likely to exceed 50% for the whole literature.

- Solutions

- Make data, materials (analysis code) more widely and openly available

- OpenNeuro.org, Human Connectome Project, Databrary.org, etc.

- Reuse shared data (e.g., Adolescent Brain & Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study)

- Increase sample sizes, improve detection of small effects

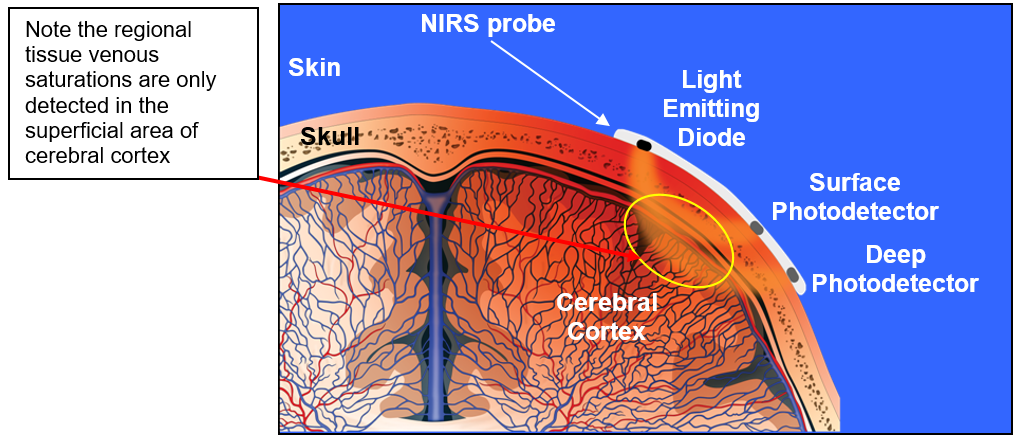

Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS)

- Near infrared light penetrates scalp and skull, refracted by brain tissue

- Returned signal altered by blood \(O_2\) levels

- Time course (temporal resolution) ~ BOLD fMRI

- Spatial resolution low

- More suitable than fMRI for pediatric populations (less susceptible to movement artefact)

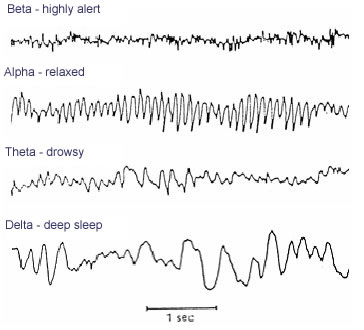

Electroencephalography (EEG)

- How does it work?

- Electrodes on scalp or brain surface

What does EEG measure?

- Voltage differences between source and reference electrode

- Combined activity of huge # of neurons

- Current/voltage gradients between apical (near surface) dendrites and basal (deeper) dendrites and cell body/soma

Collecting EEG

Evaluating EEG

- High temporal, poor spatial resolution

- Analyze activity in different ‘bands’ of frequencies (via Fourier analysis)

- LOW: deep sleep (delta or \(\delta\) band)

- MIDDLE: Quiet, alert state (alpha \(\alpha\) band)

- HIGHER: Sensorimotor activity reflecting observed actions? (mu or \(\mu\) band), (Hobson & Bishop, 2017)

- HIGHER STILL: “Binding” information across senses or plasticity? (gamma or \(\gamma\) band), (Amo et al., 2017)

Brain Computer Interface (BCI)

- Based on EEG/ERPs

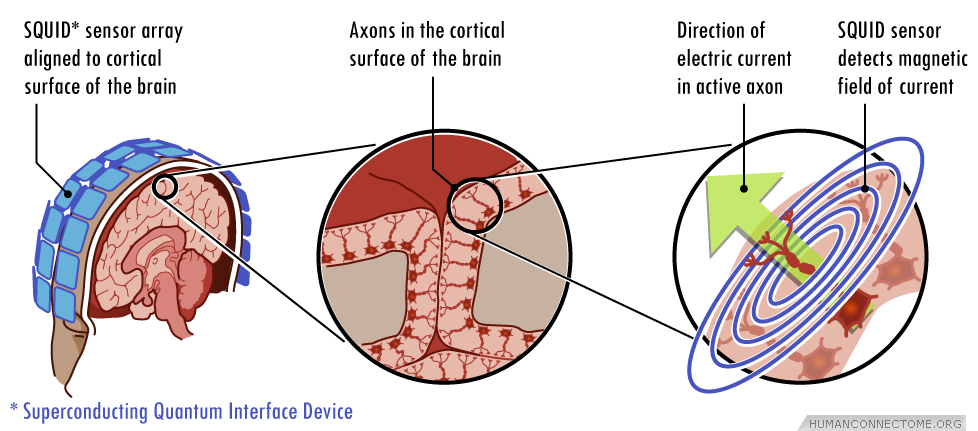

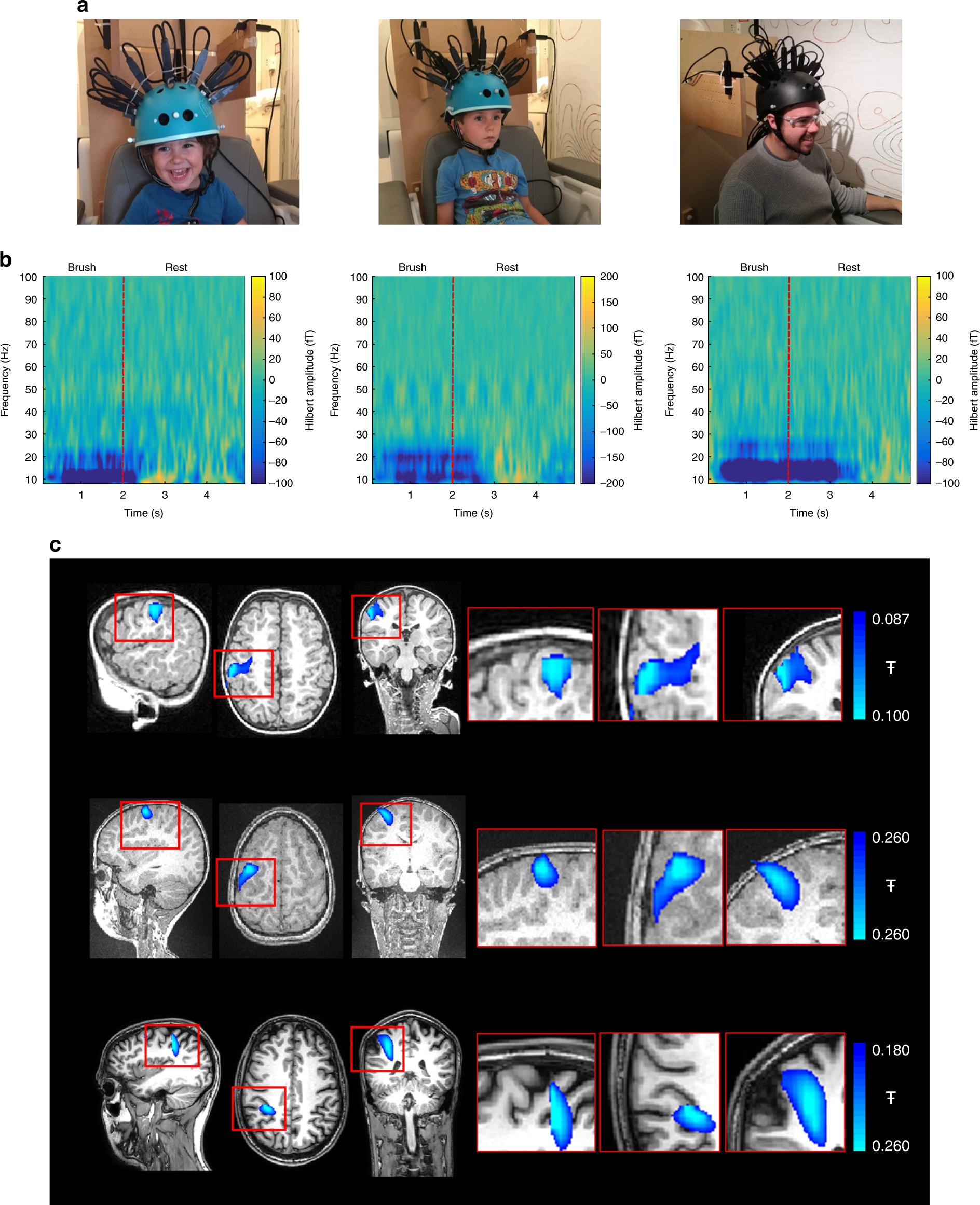

Magneto-encephalography (MEG)

- Like EEG, but measuring magnetic fields

- High temporal resolution

- Magnetic fields (\(\vec{B}\)) propagate w/o distortion

- But oriented orthogonal to electric field (\(\vec{E}\))

Strongest signals from sulci \(\perp\) to cortical surface

vs. EEG that favors signals from neurons \(\parallel\) to cortical surface

Requires shielded chamber (to keep out strong magnetic fields)

++ cost vs. EEG

New device minimizes problems with motion

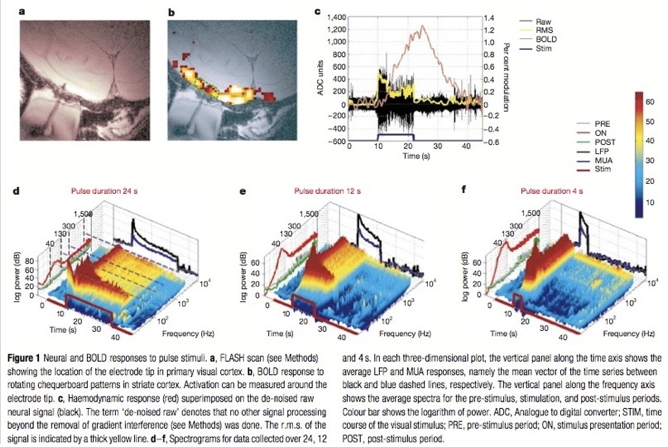

How do EEG/MEG and fMRI relate?

- BOLD fMRI likely reflects presynaptic (afferent) input to area

- EEG/MEG likely reflects postsynaptic (efferent) response to those inputs

- (Logothetis et al., 2001; Logothetis & Wandell, 2004)

Manipulating the brain

- Interfering with it

- Stimulating it

Interfering with the brain

- Nature’s“experiments”

- Stroke, head injury, tumor

- Neuropsychology

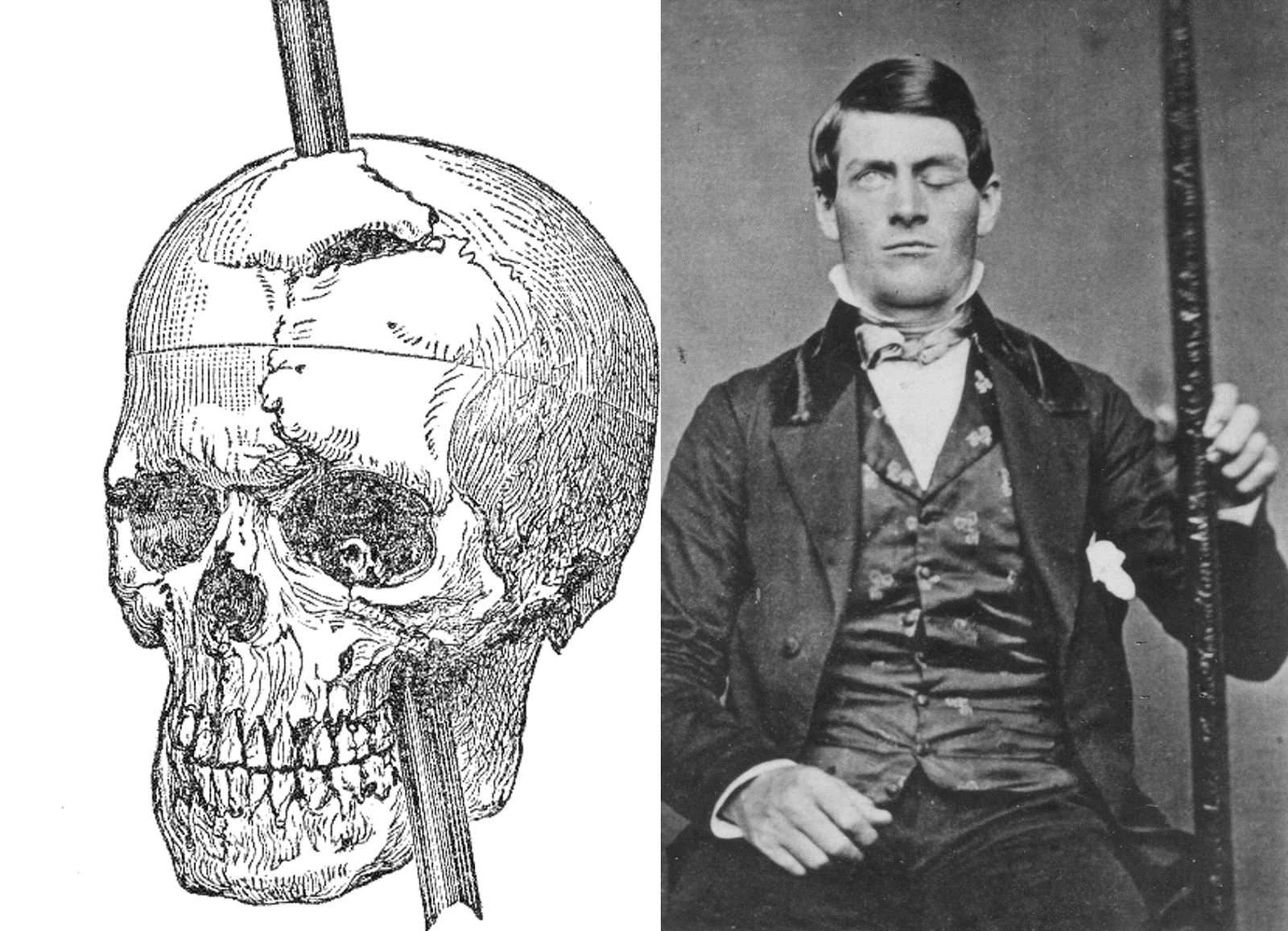

Phineas Gage

Evaluating neuropsychological methods

- Logic: IF damage to area X impairs performance, THEN region critical for behavior Y

- Double dissociation: Damage to area Z leaves behavior Y intact

- Weak spatial/temporal resolution

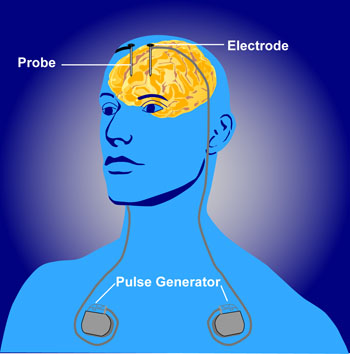

Stimulating the brain

- Electrical (Direct Current Stimulation - DCS)

- Pharmacological

- Magnetic (Transcranial magnetic stimulation - TMS)

- Spatial/temporal resolution?

- Assume stimulation mimics natural activity?

Deep brain stimulation as therapy

- Depression

- Epilepsy

- Parkinson’s Disease

Optogenetics

https://www.youtube.com/embed/I64X7vHSHOE

- Gene splicing techniques insert light-sensitive molecules into neuronal membranes

- Application of light at specific wavelengths alters neuronal function

- Cell-type specific and temporally precise control

- Mimics brain activity

Simulating the brain

- Computer/mathematical models of brain function

- Example: neural networks

- Cheap, noninvasive, can be stimulated or “lesioned”

Or synthesizing one…

Human brain organoids

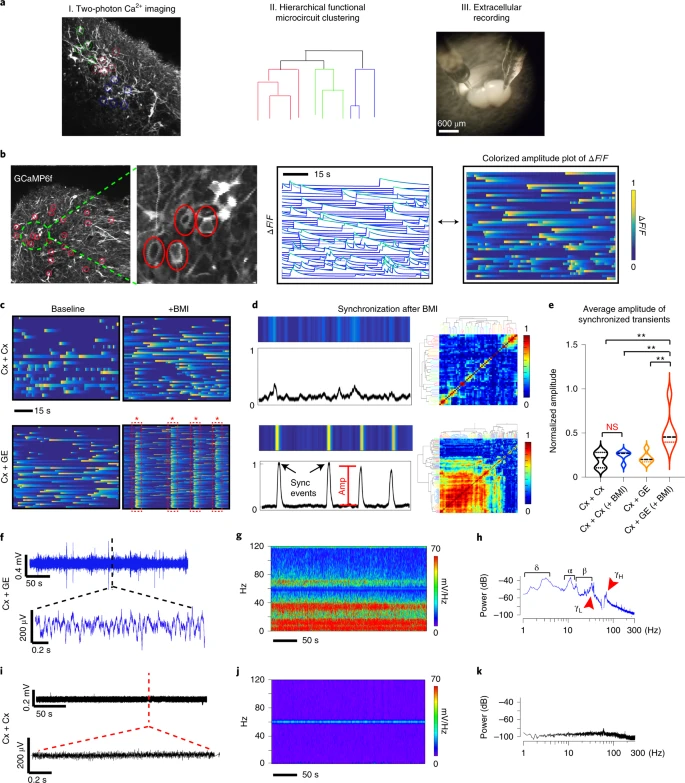

Brain organoids represent a powerful tool for studying human neurological diseases, particularly those that affect brain growth and structure. However, many diseases manifest with clear evidence of physiological and network abnormality in the absence of anatomical changes, raising the question of whether organoids possess sufficient neural network complexity to model these conditions. Here, we explore the network-level functions of brain organoids using calcium sensor imaging and extracellular recording approaches that together reveal the existence of complex network dynamics reminiscent of intact brain preparations. We demonstrate highly abnormal and epileptiform-like activity in organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells from individuals with Rett syndrome, accompanied by transcriptomic differences revealed by single-cell analyses. We also rescue key physiological activities with an unconventional neuroregulatory drug, pifithrin-α. Together, these findings provide an essential foundation for the utilization of brain organoids to study intact and disordered human brain network formation and illustrate their utility in therapeutic discovery.

![(Figure 3 from Kantonen et al., 2021). The blue outline marks brain regions where lower [11C]carfentanil binding potential (BPND) associated with higher External eating score, age and PET scanner as nuisance covariates, cluster forming threshold p < 0.01, FWE corrected. In the red–yellow T-score scale shown are also additional bilateral associations significant with more lenient cluster-defining threshold (p < 0.05, FWE corrected) for visualization purposes.](https://media.springernature.com/full/springer-static/image/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41398-021-01559-5/MediaObjects/41398_2021_1559_Fig3_HTML.png?as=webp)